|

Prototype seems to be one of the most misused words in manufacturing. An early working example of a concept is often referred to as a prototype; however, a prototype is actually the final design on which the manufacturing is patterned, the last design before you start to manufacture in volume. From Webster’s dictionary “a first full-scale and usually functional form of a new type or design of a construction”.

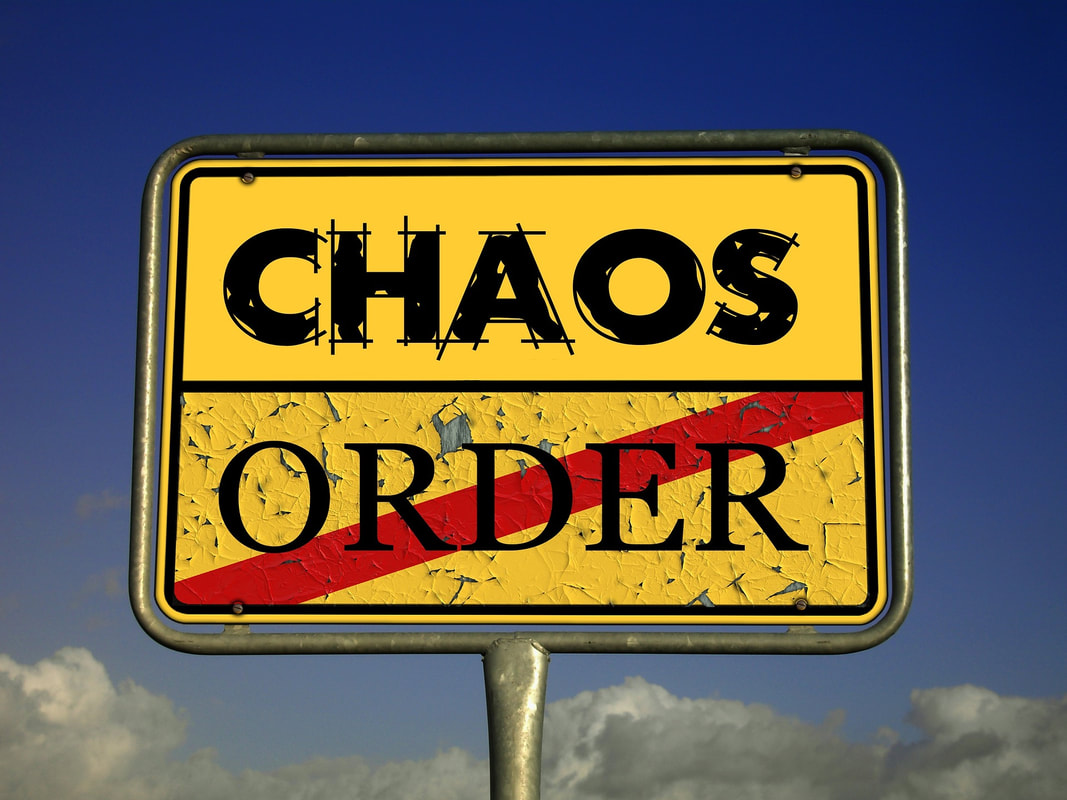

This early conceptual design is a proof of concept and is a totally necessary step to show that an idea is valid, determine if there is sales interest, and to test engineering ideas. Too often though, we see companies come up with a conceptual design, build a proof of concept and believe that the design is done and that they are ready to take the idea to production. Conceptual design is very much a creative activity and creativity cannot always be rushed. However, if the requirements of the product are well understood, knowing who the stakeholders are and what constraints must be met, conceptual design can avoid many issues. Creativity, however, does not negate good planning. Lean principles can still be used to plan and efficiently execute conceptual design. A good proof of concept needs to test if the potential product merits development. It will likely help determine how the final product will look, what features are required, and how they all fit together. It’s a learning step to help specify the product. There could many iterations, and it will focus on defining and confirming the requirements, but not on how it will be built. The final proof of concept should define the product requirements. The next step is to understand how to turn it into a product, something that can be built in volume repeatedly. Prototype design will take that conceptual design and figure out: how best to fabricate custom parts; what purchased components are suitable, available and at what cost; and how to assemble, package, ship and service the product. The necessities of cost and schedule will often dictate how much of the proof of concept design has to be modified. The final product will likely be a set of compromises from what was envisioned to what is practical. Both steps are essential. Both steps require different skill sets and input from different stakeholders. They both take time to do properly. So, it’s natural to want to skip some or all of the process, especially in a young company where budgets are tight. Every idea needs to be fully defined and vetted to ensure it meets the business needs. It’s the prototype that defines the final configuration and how that idea can be built and sold - and how profitable it will be. In part 1 of this series I discussed some fundamental ideas and approaches required to start from scratch and build a supply chain system. If you take those to heart, you will find that you are immediately confronted with incredible, unlimited complexity and variability around what to do next. I call this chaos, that which is unknown, impossible to know, and virtually impossible to plan for. In an early-stage company, or at the earliest stages of any product development, chaos is all that exists. Chaos can present itself to organizations as:

We are told that we need to plan, set rules, buy technology, and invest capital with the promise that we will eliminate chaos. But how do you eliminate that which is unknown and impossible to know? Embrace the chaos We are taught to view chaos as a bad thing. I argue that creativity in its purist form is chaos, and no innovation or leap of progress can be made without it. A music composer takes infinite complexity, the unlimited chaos of sounds, colours, and emotions and blends them into a masterpiece. Successful businesses don’t spend much time trying to avoid chaos, instead they manage those things that are within their control and build processes that can respond ever quicker to changing complexities and those things they can’t control. Life is chaos, to attempt to live life chaos free is futile. If you are at an early-stage and building a supply chain from scratch, then you owe your very existence to chaos. Your new firm or product idea was born because existing companies or products failed to respond to some changing need, some complexity, some type of chaos. It is up to us to embrace and harness the power of chaos. A balance between order and chaos In part 1, I mentioned that you need to focus on those things which you can control. Those controls are required to ensure that your firm operates consistently, predictably, with known costs, benefits, and measurable progress for any given activity. In supply chain, this means that there is a hierarchy or universal organization of elements which must exist (and must exist as an interactive system) before any of those elements can function well. Back in the day, we referred to it as “the planning hierarchy”. My former professor and mentor, the late Lloyd M. Clive (co-author of the seminal book “Introduction to Materials Management”) used to tell me “tattoo that hierarchy onto your brain, and you will be able to navigate any conceivable supply chain challenge". After 20 years of testing that assertion, I can confirm that he was exactly right. However, and this is critical, this structured approach should not be applied to prevent chaos. Instead, consider that it is required to bring your focus where it needs to be to consistently and predictably manage what is known while also harnessing chaos by providing a system flexible enough to learn and adapt on a dime. Processes for process’s sake – an unmeasurable waste I have seen countless firms build process upon process, implement technology upon technology, in order to “improve performance” without consideration of the overall business case, or without a system thinking approach. This approach is flawed. The inevitable outcome is a strict, inflexible set of policies and processes which do the opposite of perform, they absorb capital and time (an unrenewable resource) and most often end up existing for the sake of existence. We’ve all just witnessed a great example in real life with young start-ups pivoting to fill PPE needs faster than the well-established firms could react, and go on to prevail in delivering value to their customers. Start-ups are full of chaos (unlimited complexity), while mature firms are full of order (constraints applied to reduce complexity). But its chaos that demands order to constantly evolve. The planning hierarchy need not be complicated, in fact its better if it's not. It should be continuously measured and reviewed against the business case, to ensure that it is controlling that which can be controlled, predictably and reliably. And the business case should be continually measured against performance to the customer needs. Anything beyond that is waste. Early-stage firms will require only basic elements in their planning hierarchy, and if any of them become more effort to manage than the benefit they provide, you have to consider that it may be going too far. Consider Continuous improvement, a well-known (and important) part of effectively managing process. But if there is a shift in the business case, or processes are no longer supporting the business case (ex. dominant focus on local-level performance metrics instead of system-level) firms are at risk of creating more waste in continuous improvement instead of improving performance. Dr Russel L. Ackoff, a pioneer in System Thinking once said “Continuous improvement isn’t nearly as important as discontinuous improvement.” And indeed, he was right. Discontinuous improvement is chaos. It is step-function change, as opposed to gradual ongoing improvement. It’s also the ability to pivot and adapt quickly when conditions or requirements change unpredictably, or when the customer demands it. For early-stage companies, the adoption of process controls and best practices is not nearly as important as adaptation of principles to the specific situation of the firm or the product. Putting it together I usually tell those who are building a supply chain from scratch, to embrace the chaos but keep that seatbelt on. Process and a hierarchy are required to reduce the chaos to manageable terms, but the key is to adapt these to the firm's needs, not to adapt the firm to the process needs. If viewed with a system thinking mindset, the task of balancing chaos with order will be dictated by how well the firm understands and delivers to its customer. Chaos allows the firm to be creative, and well-developed order allows the firm to quickly adapt to changing conditions with greater speed, ease, and repeatability However, it’s critical to remember that the customer is the most important part and process must never consume more than the value it delivers. In my next post, I’ll explore the planning hierarchy in detail and how it becomes the foundation for any firm’s supply chain (and operations), and how it can be adapted to early-stage firms. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 - The Bill of Materials - The Journey is At Least As Important as the Destination Part 5 - Supplier Management  As applied to organizational improvement, system thinking is grounded in the following fundamental principles:

System thinking takes a birds-eye view of how the firm is employing the resources it has invested in in delivering value to its customers. System thinking posits that a firm’s resources do not operate independently, but work together in an interconnected and interdependent fashion, not unlike the musicians in a world class symphony. System thinking focuses on aligning and synchronizing the flow of activities among and between each resource as they collaboratively work together to create and deliver ever-increasing customer value. When should we use a system thinking approach? Any organization interested in improving its operational and financial performance should employ system thinking. System thinking is a different way of viewing and thinking about how your organization creates value for the customers that buy your products and/or services. In a business environment, system thinking focuses on delighting the customer by significantly improving flow in the value creation stream in your firm. The focus on customer value creation distinguishes system thinking from conventional cost-driven management approach. Simply stated, cost-driven management breaks down the organization into its individual resources, products and services, then focuses on driving down or optimizing the cost of each resource in isolation. Unfortunately, this approach not only results in sub-optimal system performance but also ignores the only part of the system which generates cash inflows and future growth, the customer. System thinking as a best practice focuses on aligning and synchronizing the activities of all resources in a system. In the process, waste is eliminated, lead times are shortened, labour is freed up, capacity is released, costs are reduced, operational and financial performance is improved, and the firm becomes increasingly competitive. This approach will also effectively reduce a firm’s carbon footprint by reducing the production of greenhouse gases through the elimination of wasteful non-value adding practices. Organizations are constantly facing new challenges, and the future is unknowable. The current pandemic adds additional layers of complexity and volatility into an already challenging hypercompetitive marketplace. As a manager or business owner it can be overwhelmingly difficult to determine what the next step should be for your business in this increasingly complex environment. System thinking helps clarify and simplify the way forward. If your organization is struggling with any of the following issues, system thinking can help.

BKW’s Business Alignment Program BKW can help you resolve the challenges you are facing, and help you insulate your firm from the myriad of complex challenges you are faced with every day. Our Business Alignment Program based in system thinking is a proven approach. It will help you to identify hidden opportunities, release untapped capacity, and improve your business’ resiliency. If you are a small to medium sized manufacturing firm and anything you’ve read above resonates with you, we can help and would like to hear from you. Please click the link below to provide us with some preliminary information and BKW team member will contact you to discuss how we can help. Click here to contact the BKW team. “How do I establish a supply chain? What are the most important elements of a supply chain for a start-up or early stage company? How can I build supply partners when I don’t have any volume yet?” These are the most common questions that I hear from start-ups and early stage companies, and they are excellent questions! How do you create a supply chain when you have very few people, minimal resources, low volume, and next to no budget? In Canada more than 90% of our manufacturing firms are Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), and that number is growing rapidly. Unfortunately, most supply chain discussions and methodology are focused on improving already existing operations for larger firms, often with more capital and higher volumes of production than the majority of SMEs. As an entrepreneur, this is incredibly frustrating. From a supply chain perspective, a business that bases its revenue on producing tens and hundreds of something can be harder to manage than continuously improving an established supply chain that has scaled to mass-production due to the extreme variables in cost, time, customer and supplier terms, etc. Although, with the onset of COVID-19, even the well-established methods being put to the test. Shifting consumer values and economic conditions are changing the way companies produce - high-volume, low mix/value production is giving way to low volume high mix/customization/value products and services. Here in Canada, we are well positioned to be global masters of low volume, high value products. Products in this category include items such as mission critical medical devices, scientific equipment, and consumer goods designed for a market where longevity, quality, and sustainability are prioritized over cheap and disposable products. However, this model is infinitely more complex with far more variability than traditional high-volume manufacturing. Building a supply chain from nothing is an entirely different science than anything that applies to the mass-manufacturing world. Today I’ll give you my 4 best tips for establishing your supply chain. 1) Focus on What You Can Control If you find yourself in a company that’s establishing a supply chain for the first time, then odds are that you have some sort of business education or career experience. You may have formal supply chain training, as I do. If that experience has been focused on well-established supply chains, you may find starting from zero to be an overwhelming proposition. Worse, if you are rigid in “how it should be done”, you may find that it’s almost easier to forget what you know than to try to determine how to apply it to completely different circumstances. Traditional standards and best practices from large or well-established firms and/or mass manufacturers are often just not practical for early stage or low volume/high value producers. Today with COVID-19, business conditions can change hourly (forget daily) and that level of variability can’t be met with incomparable past experience. So, the first step is to shift to a mindset that doesn’t try to control variables that we can’t (with incomparable experience) and instead focus only on that which we can control. We do this through system thinking and evidence-based decision making. 2) Understand that Supply Chain is not a thing or a standard, it’s a result that is dynamic and constantly changing. Supply Chain is a result, not an independent function or activity. It is the result of several cross-functional business processes and how well (or not) they work together. You can’t build or refine a supply chain as an individual entity; you must build better business processes and integrate them with a system view (focused on the business case and delivering customer value - or not producing anything customers aren't willing to pay for) which will result in better supply chain performance including resilience and agility. That’s not to say that supply chain will “build itself”, but rather what you do build as supply chain can only be as good as the business processes to which its connected, and all of it only as good as the whole-system view and value chain. This is why Supply Chain is a strategic function, despite common ideas that it’s a transactional or administrative function. Supply Chain is the ultimate measure of your overall business system in real time, and your focus on delivering value to your customer. 3) Supply chain begins long before you have a physical product. I’ve often seen firms get a working prototype and announce that they are now ready to consider supply chain and manufacturing, only to find out that much of the work they have done must be undone and redone (at the expense of time and cost) because what they developed is not manufacturable or able to be supported with supply in the volumes, costs or quality required. The resulting delay to market or unplanned capital requirements can be deadly. In reality, your supply chain considerations begin sometime after someone has a product idea but before its first iteration is scribbled on a napkin. You need to have input from professionals within the various disciplines that are collectively called “supply chain”. As a new product idea iterates from vision, to napkin, to proof of concepts to pre-production prototypes, the supply chain iterates also and in parallel. To me, it can’t be anything other than a fully integrated development cycle. While the product designers, engineers, product managers, marketers and sales team are working to create a product that a customer is willing to pay for, supply chain folks (sourcing, purchasing, logistics, materials/inventory/production management) as well as potential suppliers (for individual products, or contract manufacturers) must weigh-in to advise what is possible to produce within the constraints of cost, materials availability (short and long term) lead time, as well as international trade concerns, shipping regulations, quality standards, etc. The supply chain begins as an evolution of an idea, grown by the acquisition and validation of information and resources that are ultimately tuned to the business case and customer demands. It identifies areas of risk, and often facilitates negotiation and trade-offs between different areas/interests in a firm to arrive at the best and most viable outcome from an execution point of view. If all the functions involved have done their due diligence along the way and validated customer needs against identified constraints of delivering those needs, the end result will a manufacturable product that provides value the customer is willing to pay for. It is important to note that there are two customers to consider - the external customer who buys, and the internal customer who depends on information. Access to these professional skill sets can be tricky for early firms, in many cases it can be far more economical to hire professionals on an as-needed basis so long as you understand how to properly integrate those resources within a system thinking framework that supports your business case. 4) Remember Everything You’ve Learned but Keep an Open Mind While in step 1 above it may have felt like it would be better to forget everything you know, in this step you may realize that you have the opportunity to apply portions of your past experience that (with testing, modification, or improvement) may be adaptable to this new product or business case. And other portions may be completely inappropriate to the specific business case and should be left behind. But until you are ready and willing to throw it all out in favour of a wide-open mind, then you are subject to the same old enemies of progress: “I’ve always done it this way”, and you cannot see the opportunities that lie hidden in the knowledge gaps that everyone has, which are uncovered through collaboration. This shift in mindset is the single biggest factor that will make or break a young company or product, because it limits one’s ability to adapt old knowledge with the present conditions, and create new knowledge and experience that is highly relevant to the firm right now and down the road. While it sounds trivial, its actually harder than one may think. In a future blog, I’ll discuss the most important functional elements required to establish a supply chain system from scratch, in any firm. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 - The Bill of Materials - The Journey is At Least As Important as the Destination Part 5 - Supplier Management COVID-19 has caused massive disruption. No matter the industry, every business has been reassessing, changing plans, and trying to find their way through the uncertainty. Manufacturing had already been evolving, but in the wake of this global pandemic manufacturers need to change incredibly fast in order to survive.

Global trade has seen escalating tariffs, supply chain shortages, and closed borders. Advances in technology are accelerating, resulting in product and industry life cycles becoming even shorter and shorter. And on top of all that, social media is amplifying the good with the bad, resulting in escalating customer expectations. For years competitive manufacturers have known that their products must have a complementary service component to support the product. This has become even more prevalent with all this disruption. It’s no wonder traditional goods producing firms are finding it harder to sustain their competitive advantage. How can manufacturing firms keep up with all of this change? Time has always been an important factor for success. Now, time is the competitive advantage. Firms need to look at their agility, ability to innovate, and the timeliness of their analytics if they want to keep up with their customers. Agility If we have learned anything from COVID-19, it’s that businesses need to be able to pivot. This applies to employees, capital equipment, supply chain, the whole team. In other words, firms must pivot not just one element of their business but their entire “system” to create and sustain a competitive advantage. Examine those firms who were able to pivot their production to needed medical supplies, equipment, or PPE. They were able to keep their teams working and ultimately supported the front-line workers. Firms who have agility can recover faster and with higher quality of results, for themselves and their customers. Successful businesses collaborate. By fostering relationships with employees and suppliers we can create partnerships rather than strictly transactional relationships. Allowing employees room to experiment can generate agility through increased knowledge and understanding. Using this same approach, we can turn suppliers into partners, they work with us to deliver success. After all, it is a “system”. How quickly can your business scale to meet increased demand? If your company cannot keep up, customers will move on. When looking at capital equipment, flexibility is critical. Assessing your entire operation for additional capacity can show how changing certain aspects can reduce waste and deliver higher value. If your firm can scale quickly, faster than competitors, then you have an opportunity to keep their customers, perhaps forever. Innovation There are three key sources of innovation for a company – employees, supply chain partners, and the customers. Employees are a company’s preeminent resource. Not only do they know the products inside and out, they understand all the details of the equipment that makes it. They must be partners in development and improvement. Their tacit knowledge gives insight that can lead to incredible innovation and efficiency, if given the opportunity. Supply chain partners can be another source of innovation. Once again this is where a deeper relationship allows for better understanding rather than simply fulfilling orders. Capturing their tacit knowledge can be a game changer. Take the time to listen to your customers. Find out what makes your customers successful and ensure your product is fulling actual needs. Listening and adapting with customer feedback is a key component of service, and an additional source of competitive advantage as service is a very difficult for a competitor to copy. Monetizing your customers’ tacit knowledge results not just in better recurring business but a stronger sustained competitive advantage. Analytics Data leads to decisions. While most businesses track a number of different statistics, unfortunately many of these are not measured immediately (financials are a good example of this). Businesses need to focus on what they can do right now. Start by measuring one day – Were all of the orders that came in fulfilled today? Was there any excess capacity? Could there be? By using timely data, businesses are in a better position to adapt to changing conditions. The trick is to find those leading measures that link directly to lagging measures such as financial performance. The manufacturing industry is rapidly changing. Firms that are agile, innovative, and able to access timely data can position themselves to successfully evolve. Please remember - many ideas may fail, but you have to keep trying! By looking ahead and experimenting, your team gains valuable knowledge and will be ready when it is time for change. Bottom line, time is the only resource that, once used, cannot be replenished. Agility, Innovation and Analytics optimize the time that your firm has. With COVID-19 restrictions closing most offices, many of us had a few months trying to navigate working from home. By now, some of you may have returned to your place of business, and while I am sure it has changed quite a bit to the way things were prior to COVID-19, it is different than working from home.

I am not going to talk about the technical challenges or the furniture and space required of setting up a home office. There have been many great articles written about this and chances are you read them when you first started working from home. I want to discuss how working from home has been for you, what challenges it has brought up, and possible ways of creating a better experience for you now and in the future. Let’s start with one of the obvious differences: Distractions. I am home. My wife or partner is working on his/her own project and occasionally needs my input or wants to share his/her thoughts. What is the BIG deal, right? What about having your kids run around? They are likely home as well and expect to be entertained. Throw in a dog or a cat, and calls from friends and family since they are not working and seek your attention. And of course, one of the biggest distractions – ME. When I’m at home in my own space, “I get to make tea or coffee whenever I feel like it, have a snack here and there, make lunch, watch a bit of TV (just one Netflix episode…), or listen to music or the radio. Oh yes, then there are all these other chores I have on my to-do-list. Why not do some of them since I feel like it and taking care of the garbage only takes a few minutes anyway, right?” In other words, working from home can create the perfect storm when it comes to distractions. It can be difficult to get any work done. Are you someone that is getting easily distracted and pulled away to other tasks and opportunities? Or maybe it is the other way around for you? Let’s take a look at that. While you are typically focused and disciplined at work, meetings and interruptions are frequent. Perhaps working from home is a blessing in disguise. “Finally, I can concentrate on my work without anything or anyone getting in my way. Hey, I might even work 10-hour days. My plate is so full that I could use that extra time to clean up my backlog.” Speaking for myself I can get so focused that all of a sudden, I missed a meal or two, being far away in la-la land and hardly approachable. Being in the zone and deeply concentrating can provide a great amount of satisfaction, however, over a period of time there is a good chance that fatigue and tiredness sets in, if not even burnout. Finding Balance Working from home can be a wonderful thing for both, you and your employer If you can find a way to balance both work and your personal life. Getting sufficient work done to keep your project moving forward, to show good performance, and taking time for yourself, your family, and your friends. Here some ideas you can think about. Answer these questions for yourself. Make a plan, and do your best to stick to it. Present your plan to your loved ones and/or negotiate with them to create a win-win for everyone.

What are your biggest challenges around working from home and how you have been able to make this work for you? I’d love to hear your thoughts or questions, feel free to reach out through the Contact form. Knowledge Transformation and Digitalization of Supply Chains More and more these days we’re seeing a call for digitalization and AI adoption in supply chains. COVID-19 revealed the weaknesses inherent in global supply chains, and the call has gotten louder. With that, the onslaught of folks pushing their wares has begun…everything from small apps to large enterprise level solutions promising to revolutionize your business and make your supply chain “resilient” or “risk proof”. It all sounds alluring, and awesome. I can’t think of anyone who wouldn’t want to take advantage of anything that will help get their operations back up and running. But as we get caught up in the excitement, we may not spend the time to properly consider options, and consequences. When the excitement wears off, the realities may seem far less appealing over the long term. Why – is it a mistake to look to technological solutions? Did our selected provider lie? Are many of these solutions just gimmicks? The answer is a firm “No” to all these questions. Caveat Emptor Caveat Emptor is the most ancient supply chain principle. It’s Latin for “Let the buyer beware”. It means that ultimately, responsibility rests on the purchaser to check something out thoroughly, perform diligence and investigate all data before acting on a purchase, and if any of this is omitted, then the buyer will likely end up unhappy with the results. Perhaps this concept has become more relevant than ever. At a macro level, our supply chains didn’t fail the COVID-19 stress test because of any lack of digitalization or AI. They failed because of a lack of sufficient knowledge to build strategic and resilient supply chains in the first place. Moving from a macro to a micro level, this translates into operational problems at firms: costs that are hard to manage, expedites and late shipments, shortages in supplies and materials, lowest unit-cost decisions, inability to determine total costs including process costs, and many more. The lack of knowledge, not a lack of technology, places supply chains in a purely reactive state (always too late) instead of it being a strategic asset (always ahead of the challenges). And this is what needs to change before firms will get ahead of the curve - regardless of technology. The good news is that it can change, with leaders emerging everywhere to help guide the knowledge transformation. These are my four steps for firms that are considering digitalization: 1) Get your house in order first Well-built technology tools are absolutely accelerators. However, it’s up to firms to make sure their operations and supply chains are up to the task BEFORE implementation. This is not a new concept. ERP, which has been around for decades, typically requires anywhere from 9 months to a year of whole-company organization before it ever goes live for this very reason. And every failed ERP implementation I’ve ever seen or been asked to correct, has been a direct result of firms short-cutting or skipping this portion entirely. It’s far more economical to get your firm in order first and not expect digitalization to do it for you, that’s not its function. Reputable providers of digital and AI solutions geared for supply chains actually don’t want you to buy their products until you’ve sorted out what you supply chain needs to look like thoroughly and accurately, according to your specific business requirements. Why? As one of them explained to me, “Our solution is a Ferrari. It will accelerate what the user applies it to exponentially. If the user applies knowledge and experience it will do incredible things. If it’s applied to a bad set-up it will become exponentially bad, exponentially quickly, and with a lot of cost. If we sell a Ferrari to someone who doesn’t know how to drive…it will look great and maybe even go really fast for a short while, but it will end up in disaster and our customer will blame the software. We’d rather see the customer be successful and our tools be a part of that success.” 2) Use external parties to give you an unbiased view If you’ve read this so far and said “we’re in great shape, we don’t need to sort anything”, then it’s time to get another firm to do a detailed analysis of your firm to validate what’s real and what’s perceived. Preferably, not the same firm that you will buy your digitalization solutions from to avoid product bias. All firms have built-in internal bias due to departmental metrics, goals, and targets which often may support the individual departments (and even contradict other departments) instead of the business as a whole. The only way to overcome this is to use an external party not bound by any of those metrics (or compensated on meeting those metrics) who can apply an integrated system thinking approach to the business and guide re-alignments where needed without any internal bias. 3) Allow only validated data to guide the technology solution selection If you’ve done 1 and 2 above you’re now in a position to take the validated data and really understand what the core needs of the business are, without distraction of “symptoms” and “fires”. You can now look at solutions that will, when applied appropriately to your specific business needs, reduce or eliminate your pain points and allow you to increase your capacity or bandwidth (depending on the nature of the technology tool in question). Technology cannot ever be a replacement for knowledge in any business. It can however be an accelerator, freeing up resources to allow redeployment of those resources on higher-value functions to support the business case. Expecting technology to help manage your business is a great approach. Expecting it to do it for you leads to trouble. 4) Be mindful of your technology landscape and develop a strategy I once knew of a firm that had 17 different software solutions for different aspects of their business. It was a nightmare. The firm began to hire folks to keep up with the double and triple data entry these separate tools required, and it snowballed from what started as a way to minimize costs, to something that increased their costs 10-fold and nearly eliminated their capacity to actually deliver to their customers. All the while, there was no consistency or accuracy in the data provided by these separate tools. Though this sounds extreme, it can happen more easily than you think, especially among separate departments. The best practice is to develop a technology strategy from the outset. Your technology strategy should work to centralize your data and make sure all areas of the organization are getting the same numbers. Well-tuned enterprise systems are good for this, and they are accepting more “plug-ins” that allow you to add functionality from different providers without decentralizing your data (or access to it). We are truly beginning to see an integrated, system thinking approach where technology solutions are concerned. But we humans still need to do the hard work of selection, implementation, evaluation, management, and adaptation of technology wisely, as we still possess the most advanced technology in the known universe - that which lies between our ears. Technology is neither good nor evil, it is only what we make of it. If we have a bad experience with an implementation or a specific piece of software, we really need to take an unbiased look at the underlying business conditions before we blame the tool. Caveat Emptor. We’re living in interesting times. Presently, companies of all types and sizes are scrambling to figure out how to survive, and how to successfully restart their operations thanks to COVID-19. Social media platforms have been inundated with information. Some helpful, some, well…not so much.

Just before the pandemic, these same sources were filled with starkly different messaging: You need to go faster, cheaper. You need to buy this software package. Lists of things you need to buy, types of people and consultants you must hire, otherwise there will be world-ending consequences for your business. Then my all-time favourite myth – manufacturing is dead. Well, we all just realized at once, that manufacturing and supply chain are critically important to our nation’s well being and must be viewed strategically, not transactionally. Our economy, our health and our safety depend on it. Recently, I’ve enjoyed the shift in topics to discussions about how business may reinvent itself. I’ve been excited to hear and read about firms taking exceptional leaps, and even how competitors have become stronger collaboratively without giving up their respective competitive advantages. Effectively doing away with symptomatic solutions and focusing on the bigger picture for every business. Over the past 20 years I’ve worked with hundreds of suppliers from mined raw materials to electronics to food to massive capital equipment and everything in between. Yet, one supplier relationship stands out for me as I look back, as having been the most trusted, most reliable supplier I had ever worked with. They achieved this with such a simple approach that required nothing other than effort, and which any company anywhere, could implement immediately without outside assistance. This particular supplier was based in South Korea, and their business provided a technology that was not produced here in North America. There was a bit of a language barrier, but almost immediately from the first contact something became obvious – this supplier demonstrated an unwavering focus on listening to their customers. The first 6 discussions with this supplier around technical requirements and capabilities specific to the project I was involved in at the time, whether by phone or email, resulted in the same answer: “I don’t know.” We don’t ever want our suppliers to say “I don’t know”, right? Isn’t that why we contact them, because we expect them to have the answers and then once they provide them, we’ll decide for ourselves if we agree and move on to the first supplier who seems to have the right information at the right price. Or do we? In business, people feel compelled to give an immediate answer rather than make their colleague wait, or due to fear of not appearing knowledgeable. When we call suppliers, we expect them to have all the answers, even if we haven’t properly articulated our needs, or even if we don’t yet fully understand our needs. These expectations, on both sides of the conversation, set the stage for problems because we aren’t creating dialogue. Instead it becomes a transactional approach, which ultimately won’t satisfy the true needs for supplier or customer as gaps always present themselves down the road. Yet firms of all kinds will do this dance day in, and day out. As it turns out, my favourite supplier of all time almost never had the answers when first asked, and most certainly was not the cheapest. However, they were the most reliable, most honest, and had the best quality by miles. “I don’t know” was immediately followed up with “but here’s what I’m going to do to find out for you,” which was then followed up with action. He would tell me when he would respond with the information and did exactly that - on time, every time. If the question was about deliveries, he would respond on time with specific information, and goods would ship and move exactly when he said they would. If the answer was ever bad news such as “we can’t provide it to you that fast” or “we can’t meet that technical requirement”, there was no sugar coating, no excuses. Just factual information, and then suggestions for alternatives and an openness to seek creative solutions. If the answer ever required talking with someone else, he would set that up and facilitate it. That blunt honesty, followed up with demonstrated commitment to action, still remains (to me) as the most powerful value any supplier has ever offered me. And yet it's challenging to quantify at all if the measure is unit cost alone. However, in this instance I could extrapolate how much time I was saving through clear communication, virtually zero quality problems, and only one late shipment due to a labour strike at a North American port. I could also estimate the savings of avoided late penalties from our own customers, avoided lost time and delayed production, because I was able to accurately plan my own business, manage my own costs and subsequently deliver the same commitment of information to my customers. This supplier absolutely didn’t have the lowest price, and cost accounting and unit cost metrics would have insisted I dump them for cheaper options. But I estimate (with the values I can calculate) that their strict adherence to honest responses, and equally strict commitment to do what they said they would when they said they would, saved my firm 10.5 times over the cost of buying the “cheaper” alternative from other suppliers over the same time period. Today more than ever, companies could find space to survive or even scale in a cost margin that big. And that was just one supplier, imagine how much it could impact your entire supply chain. COVID-19 has caused our world to change daily. While it has been forced upon us, more and more we are becoming comfortable with saying “I don’t know”, and that opens the door for a real exchange of ideas. It sets the stage to build solid supplier relationships that are based on listening and data and not on saying what we think the customer wants to hear which sooner or later ends up costing time and money for both supplier and customer alike. I love the power of “I don’t know” for all the opportunity to collaborate and deliver real customer-focused value that follows that statement. Supply Chain professionals should continually evaluate and push to understand the multiple layers of their supply chains. Not only is it a matter of due diligence and very relevant for day to day operations, it can produce tangible benefits in the forms of risk mitigation, technical engagement, and building a socially responsible supply chain.

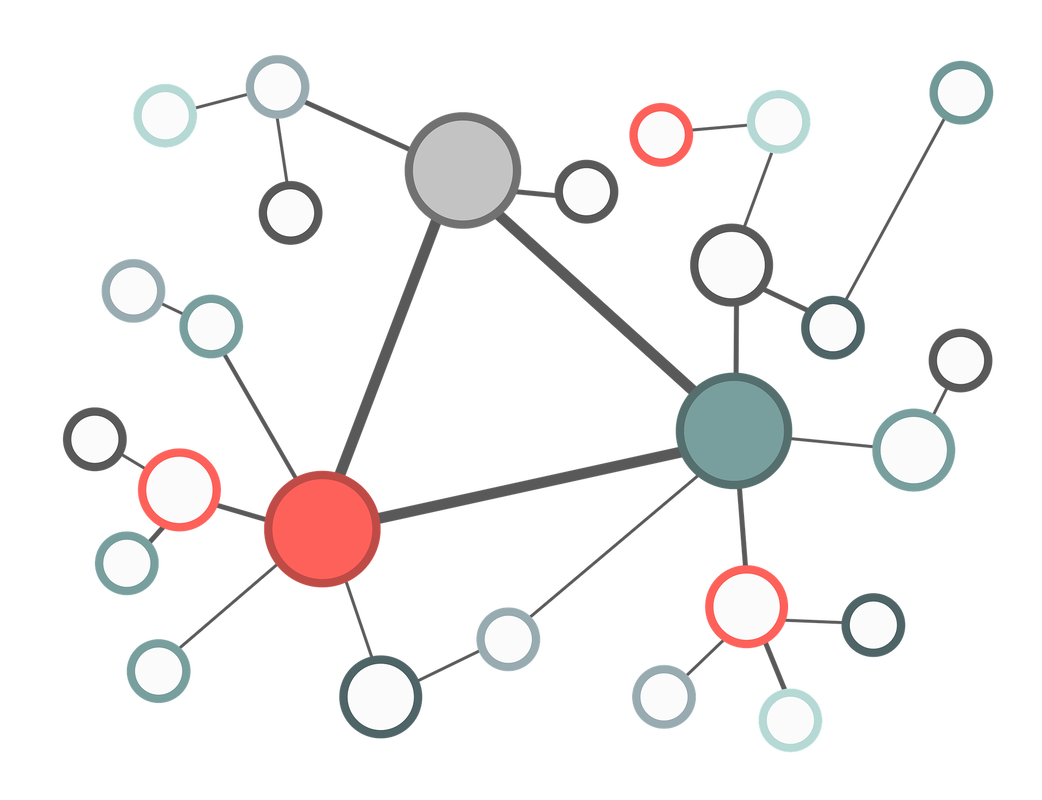

Through the start of a new calendar year when organizations reflect and refresh goals and metrics – strategy moves to the forefront. Within supply chain teams, it is a time for brainstorming ideas, charting direction and evaluating supply chain objectives. This time often results in discussion around deepening the understanding of the complex and multiple layers of supplier partners supporting the organization’s goals. Supply chain teams operating with a systems-thinking approach will often strive to connect with and understand the supply web extending out of their facility, engaging further, pulling additional information and proactively reaching out to establish connections and make introductions to their supplier’s suppliers. These initial engagements will lead to discovery of a supply chain that reached much further than previously known, both in layers of suppliers, and geographical distance. It also allows the Supply Chain team to view supply issues through a different lens with much more context, and to ask more informed questions of tier 1 suppliers when working to solve a problem. Understanding the Multiple Layers of Your Supply Chain As COVID-19 circulated the globe and supply chains started feeling the effects with extended closures of Asian businesses, and then European companies before spreading across North America, understanding multiple layers of the supply chain has become paramount. Business continuity is hinging on the ability of the supply chain to continue to support ongoing operations, and now has company-wide visibility up to the C-level. Supply chain teams that understand the tiers of suppliers and maintain relationships with critical lower tier suppliers will have an advantage in terms of faster communications, and the ability to develop mitigation plans and responses ahead of those who do not. This is starkly visible during the current pandemic but often fades to the background during normal operations – and is equally applicable during regional weather events, or instances of political or labour unrest. It must be noted that the development of these relationships does not happen quickly or easily. Often tier 1 suppliers are reluctant to divulge their own supply base, and especially to provide contacts or access to these key resources. Supply chain professionals must build an environment of trust and be clear on intentions or requirements for mapping the supply chain. Initial discussions or visits can be held between all three parties to ease any tensions. A further benefit when engaging critical sub-tier suppliers is the potential input and impact to designs, and the ability to release new designs faster. For instance, when dealing with electronic contract manufacturers, if a direct relationship exists with the printed circuit board supplier, design choices, reviews and feedback can be done much faster than working through the contract manufacturer as the conduit for communications. This could save days in a design cycle, and weeks over a new product development. It also fosters trust between all parties’ engineering teams, and can lead to the discoveries or introduction of new materials or processes. A similar approach is also true in the design of plastic or metal components, working directly with potential third-party suppliers such as tooling manufacturers or coating providers. Creating a Socially Responsible Supply Chain By understanding multiple layers of the supply chain, teams can build and employ a socially responsible approach when selecting and working with supply partners. The approach to review supplier networks for socially responsible reasons is a relatively recent development which has gained momentum after the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, and its implementation in 2012, which requires reporting on conflict minerals by publicly listed companies in the US. More recently, reporting on the carbon footprint of supply chains with the goal of becoming carbon neutral has become the focus of highly developed companies and their supply chains. Volkswagen has committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2050 in compliance with the Paris Climate accord, and other large companies are following suit. All in all, getting to know your supplier’s supplier is a critical element of strategic supply chain management. It is fundamental to the entire system, a keystone to risk management, and critical to business continuity strategies for successful companies. Engaging directly with engineering teams brings speed and new technology to new designs and brings new products to market faster. And socially responsible companies need to know who is supplying their products all the way through the chain, to build a sustainable supply chain and drive continuous improvements. COVID-19 is forcing a rapid redistribution of resources, wealth and economic mobility. Only those firms who are willing to reinvent, shift, and act quickly will survive the wave. As a small or medium business, adaptability, agility, and collaboration will be the key to your success. Here are 4 steps you can take right now:

1) Stop and assess on two horizons

We’re offering free consultations to help firms identify their current needs and next steps during the COVID-19 crisis. Our team have all navigated manufacturing operations through severe economic crisis before, and we’re happy to help and offer any other assistance we can. Give us a call at 519-588-2900 or email Matt Weller at mweller@berlinkw.ca. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed