|

Matt Weller Founder, Naviga Supply Chain In the age of technology, people, process and knowledge remain the first best ingredients to competitive advantage and innovation. Innovation is a term that gets thrown around a lot these days, but we never really mention where innovation comes from. The reality is you can’t be innovative simply because you aspire to be, nor can simply adopting technology make you innovative. It turns out that Innovation is actually the result of an ongoing cycle that despite having been well researched, is seldom discussed and (consequently) seldom known and executed. This is part of the knowledge gap I have referred to in other posts. Though applicable to any business anywhere, here’s how it works in the context of small and medium manufacturing and becoming innovative in your operations.

Tacit Knowledge: Intuitive, non-verbal. Can be individual experience or learned through imitation like an apprentice. In production, this can include all the tricks and techniques that get work done reliably and safely but aren’t documented. It can also be the key person (front line or executive) who just seems to know how to do everything or who must authorize every decision. In manufacturing, tacit knowledge MUST be converted into Explicit Knowledge (written, documented information) that can be shared, examined and refined. This eliminates “single points of failure” in processes and promotes collaboration, resilience and agility. This is the basis for effective business processes that are repeatable and productive. Explicit knowledge has a hard limit, after which no more productivity or improvement can be attained without New Knowledge. New Knowledge must always come from an EXTERNAL source mostly because any observer within a system will have biases and knowledge gaps that will prevent them from seeing the full picture objectively. New Knowledge can be as simple as an unbiased point of view outside of your business system (consultant, customer, competitors, etc.), or research based on external data. It’s not enough on its own, which is why you need Explicit Knowledge first to anchor it and to integrate with. Technology adoption can’t bring new knowledge in and of itself, but it can augment its integration when applied strategically. Innovation is the final phase and the result, not the starting point. This is when New Knowledge is successfully integrated with Explicit Knowledge to yield previously unknown advantages or opportunities in the business system. It is also a key component of true competitive advantage. Innovation can only happen after everything else, despite what may be claimed or advertised. Since it is the result of the previous knowledge processes, there is no way to skip or fast-track the road to innovation. That being said, those who take the time to extract and retain knowledge within their business are the ones who find the competitive advantages that most others miss.

0 Comments

Matt Weller Founder, Naviga Supply Chain Related links: Parliamentary Address regarding Supply Chain, SME Manufacturing and Productivity Parliament recommendation #1: National Reindustrialization Strategy Parliament recommendation #2: Realign investment and build executional knowledge This is part 3 of 3 expanding on recommendations I recently made to our Parliament around supply chains, small and medium manufacturing, and our national productivity challenges. Today I’ll talk about the need for an active, connected ecosystem for executives and leaders at small and medium manufacturing. So far, I’ve talked about the need for a reindustrialization strategy to provide coordination and focus within our manufacturing sector and our economy. And I’ve also talked about the need for changes in our education and funding models, to build executional knowledge and develop a focus on realized productivity as the primary measure of effectiveness.

But for either of these suggestions to work well, they need a feedback and adjustment mechanism within industry itself. There needs to be an active, connected ecosystem for our small and medium manufacturers where they can leverage group knowledge to solve common problems, preserving their individual time and resources to focus on competitive advantages. Or in other words, to prevent them from reinventing the wheel in disconnected silos. This bridge can serve to map, research and aggregate the needs of these manufacturers, along with the capabilities and capacities they represent (both in terms of production and employment), and provide that information in useful ways to industry groups to foster greater collaboration, alignment and focus on realized productivity gains. These groups are all critically necessary, but individually they have failed to change the downward trajectory of our national productivity. As such, it would be of critical necessity that such an ecosystem be industry led, independent from the influence of government and special interest groups, but at the same time be aware of the needs of our present and future population and our national sovereignty (30, 40, 50 years down the road) that only government has the vantage point to see beyond any individual industry. But just as individual industries cannot see the full view of our future needs, government cannot determine how it will meet those needs in isolation. So there is an opportunity for an active ecosystem to inform overarching national strategies and policy, with data, executional knowledge and most importantly, end customer feedback. I.e. employment, economics, and our population as the “market” to be served at a macro level at a breadth and scope that exceeds that of industry groups or government bodies. This is about finding out what our small and medium manufacturers need to be successful at the detailed levels (through enabling discussions, dialogue and learning between these companies), building that environment, and getting out of their way. Perhaps a simpler way to put it, an active connected ecosystem can become the glue that holds it all together in a functional fashion. We don’t have to look too far to learn how to build an active ecosystem. Canada’s tech sector has already built one, which has yielded a burgeoning tech sector that without this ecosystem, simply would not exist. Although as of late they too are experiencing challenges, because our lack of executional knowledge and our productivity crisis is not isolated to small and medium manufacturers, and as it turns out, funding scorecards do not correlate to successful businesses. But our manufacturing sector needs tech and innovation, and as such a revitalized manufacturing sector and reindustrialization strategy, can easily be a foundation on which tech can thrive and prosper in a symbiotic relationship to everyone’s benefit. A future that sees a manufacturing ecosystem equal to that of tech is a future that takes advantage of collaboration, builds east-west trade in addition to our traditional north-south trade patterns, and sustains real, measurable productivity growth and prosperity for all of our economic sectors, and for our population as a whole. Matt Weller Founder, Naviga Supply Chain Related links: Parliamentary Address regarding Supply Chain, SME Manufacturing and Productivity Parliament recommendation #1: National Reindustrialization Strategy Parliament recommendation #3: Create an active, connected ecosystem for SME Manufacturers This is part 2 of the 3-part series expanding on recommendations I recently made to our Parliament around supply chains, small and medium manufacturing, and our national productivity which is currently in crisis. Today I’ll talk about the knowledge gap, and the educational and funding opportunities to improve things. To understand the knowledge gap, some context is required. Generally speaking, Canada’s small and medium manufacturing was at its peak when I started my career in 2000. I watched firsthand as the internet age, and then global trade accelerated the speed of business and the leverage potential of competitive advantages very quickly. From a supply chain perspective, it seemed as though things went from just fine to broken everywhere within just a few short years. Our way of producing was no longer sufficient in the new economic environment.

The causes of our productivity decline in manufacturing The emergence of the internet, accessibility of global markets and trade, and economic crisis (2001 and then 2008) demonstrated that ideas are not enough, talent is not enough, we needed more to compete. We introduced industry 4.0, automation, technology, and an almost religious belief that low unit costs from low-cost countries would equal increased profits. The net result is our productivity decline accelerated exponentially, and our manufacturing sector was decimated, simply because these things are accelerators. If you’re effective, they will accelerate that and make you more efficient. If you’re not effective, they will accelerate your ineffectiveness into disaster. Our problem is not lack of technology, nor is it cost-competitiveness. The real problem is a lack of explicit operational knowledge as a strategic asset at the executive level, a lack of retention and development of that same knowledge, and general skepticism from companies that have lived through this reality just to see many solutions leave them worse off then they were to begin with. So the knowledge gap is not so much a failure to adopt new technology as much as it’s a gap in how to be effective in the first place when it comes to strategic supply chain and operations management, system thinking, and the c-suites ability to chart the course of the company based on accurate and complete information. Our executional knowledge gap of the pasts persists into our future You have to be effective before you can move on to become efficient at whatever you’re doing. There are no shortcuts. And all of our resources for SME Manufacturers have been based on efficiency, ignoring completely any support around how to be reliably, and repeatedly effective at producing. Yet, this is exactly what we don't do, teach or reward. Instead, we continue to assume that with the right tech, marketing and cash injection, everything will just work. When it has worked, it’s been closer to luck than the result of knowledge and skill. Luck is not a reliable strategy. Today, we face a new set of challenges. The breakdown of globalization and new economic crises are parallels to the early 2000’s. The emergence of AI promises to be many times more disruptive than the emergence of the internet. The past 10 years have seen strong anti-competitive influences in our economy, promoting large firms and/or monopolies, and supply chain solutions suitable to them (but not at all suitable to our SME Manufacturers) at the expense of small and medium manufacturing. Today, we punish productivity with arbitrary taxes, regulations, and governmental interference at multiple levels. Amidst all of this, we find ourselves at a time with less, not more – productivity knowledge than we had previously. This is concerning because that knowledge is our only means to ride out the storm. No other solutions can be effectively applied without it. And you do not have to try hard to find an example. During the pandemic, business leaders said Just In Time (JIT) was responsible for breaking our supply chains, showing a complete lack of understanding of what JIT is. One thing it is not, is a blind elimination of inventory that will put you at risk for any number of disruptions that may be relevant to any given business. Although blaming it is an admission that this is exactly what they’ve done, demonstrating the very lack of knowledge and strategy I’m talking about. The pandemic shortages had nothing to do with JIT and everything to do with incredibly poor demand planning and lack of strategic treatment of supply chain on a mass scale, which has been brewing for years and we’ve not seen the worst of it yet. Those who do have the necessary knowledge are retiring, those coming up behind have neither experience nor practical knowledge because (as mentioned already) knowledge around productivity in manufacturing and supply chain is largely still not taught. In this context, our obsession with efficiency-based solutions becomes peripheral to the challenge at hand, and akin to rearranging deck chairs on the titanic for many of these firms. Solutions to change course Of course, in all of this, there are opportunities. 1) We can build programs and supports focused on the knowledge cycle, from tacit knowledge through to innovation. This can be done without any technological requirements. 2) We can learn to apply a system thinking approach to business challenges with an ability to test and adapt. This can build solutions that are specific to individual companies. Generic solutions aren’t helpful. 3) Build an active, connected ecosystem for executives at Small and Medium Manufacturers that is focused on productivity ahead of all else and enables (and celebrates) realized productivity gains as well practical knowledge around productivity in SME Manufacturing. 4) Expand funding to include knowledge development and retention within these firms. Currently, funding models revolve around solving a technological problem, or adopting technology. A national reindustrialization strategy (mentioned in my last post) can anchor this. 5) We can develop programs that are accessible and affordable to SME Manufacturers that are not standardized on the practices of the 0.6% of our manufacturers (the large multi-nationals), but able to assess, understand and work within the specific realities of any given business with a focus on productivity ahead of all else. This can also be developed out of an active ecosystem. Before you can be efficient, you have to be effective. Or to say it another way, People, Process, Technology, in that order. Matt Weller Founder, Naviga Supply Chain Related links: Parliamentary Address regarding Supply Chain, SME Manufacturing and Productivity Parliament recommendation #2: Realign investment and build executional knowledge Parliament recommendation #3: Create an active, connected ecosystem for SME Manufacturers On April 30th I appeared before parliament to discuss Canada’s supply chain challenges relative to our small and medium manufacturers, and our national productivity. I brought forward several concerns and with those, three recommendations. In this post I will talk about the first recommendation which was that we create a national reindustrialization strategy, and I will expand on the other two recommendations in separate posts. From my remarks at Parliament:

“While industry must inform and lead the solutions to these challenges, a national reindustrialization strategy is needed to coordinate and prioritize those efforts and design a supply chain and business environment that is favourable to productivity. We need to ensure that we can understand, identify, and retain critical manufacturing resources, skills, capacity and capabilities and their complex interactions at the detailed levels which will be needed for both industry and consumers in the much longer term. Taking a whole system thinking approach, we can balance the needs of our economic system and avoid short term benefits to any particular sector or industry at the long-term expense of our overall productivity and economic stability. This is critical for us to survive the societal, economic, and geopolitical challenges that lie ahead, and the recent pandemic has already demonstrated our vulnerability.” Our current environment - lots of effort, no gain. In our economic environment, we have an assortment of efforts at various levels. Industry groups, industry itself, special interest groups, consumers, academia, private and government investment all exist with a disconnected or isolated view of the macro challenges at a system-wide level. They all work to solve the individual problems they were created to respond to, but they do not work to understand the integration of all these efforts collaboratively, at the interconnected macro level. In basic terms, national economic systems are “closed loop” meaning that any benefit gained in one localized area, must necessarily come at the cost of another. Without an overarching alignment or strategy, the result is a net loss to productivity and our standard of living. We are seeing this as our current reality. Our future needs demand a new approach Our future, regardless of if you subscribe to the ideas of a green economy or not, will absolutely require a massive industrial build out – at a magnitude we’ve never seen in this country - simply to retain our current standard of living, never mind improve on it. Yet currently, we are losing the knowledge, capacity and capability required to process resources and produce physical goods. The solution is to create a national strategy for reindustrialization. Such a strategy can: 1) determine what our most pressing needs will be in the future in terms of internal process capability and capacity, to preserve our way of life, national security, and sovereignty, 2) identify all players in the economic system (the organizations I listed previously) and inventory their capabilities and resources, 3) map out which groups align with the needs of the next 50 years and incentivize them to work collaboratively to fill the gaps, and 4) measure progress based on productivity and economic growth once our economic engines are driving towards the same collective goals, instead of working against each other. To be clear, there’s a couple of things such a national strategy cannot be. It cannot be partisan or hinged on a 4 -year election cycle. The needed solutions will take years to build and execute, and we need to commit to them in the longer term. It also cannot be a set of governmental decrees, or regulatory mandates. It cannot be command and control, and this is not something that can be solved with taxes and regulations. It must be voluntary, with collaboration among industry players. Government is necessary to give industry the macro “system wide” insights and incentives that individual industry players on their own can never have, but it’s industry itself that must solve industry’s problems. Which is far easier to do when there is a unified consensus of what needs to be worked on and some sense of how to prioritize the collaborative effort. SME Manufacturers at the core, but benefits for all While my focus behind this suggestion is based on our small and medium manufacturers, there’s benefit far beyond those companies. We have an emerging intangibles/innovation tech sector that is trying to find its place in Canada. Some argue that the future is the intangibles, and that tangibles (physical goods) are no longer economic drivers. The reality is that as long as there are human beings, physical products will be required, and we can either make them competitively, or be at the mercy of someone else for them. But I will argue that the physical goods economy cannot competitively or efficiently survive without the enablement that our intangibles sector can provide. They will be needed to respond to any reindustrialization strategy, to build out in ways that are competitive, efficient, clean, and robust, and enable those buildouts to iterate and ideate faster than ever before. Building a resilient economic engine both for us and for competitive export opportunities. We need our small and medium manufacturers to produce, our innovators can help them to produce better, and faster. In my view, you cannot have one, without the other. Can it be done? Without a doubt, what I am suggesting is a massive undertaking rife with multi-faceted complexities. But it is not impossible. In fact, the United States is already several years into their reindustrialization for all the same reasons, and they are not doing it for our benefit. Canada deserves to have an assured future based on its own capabilities and richness of resources. It needs to determine how to produce for itself, and not simply hope to “rent” its future needs from other nations – especially in these times of rapid de-globalization. Matt Weller Founder, Naviga Supply Chain Related links: Parliament recommendation #1: National Reindustrialization Strategy Parliament recommendation #2: Realign investment and build executional knowledge Parliament recommendation #3: Create an active, connected ecosystem for SME Manufacturers Recently, I was invited by our Parliaments’ Standing Committee on International Trade to talk about Canadian businesses in supply chains and global markets. On April 30th I had the opportunity to discuss the challenges that face our small and medium manufacturers, and why it is vital to our long-term economic future that we work to support and grow these companies.

Key takeaways include:

I offered three (3) solutions that I will expand on in future posts:

It was a privilege to participate in our Parliamentary Process! Full committee meeting here (static at start is momentary): https://parlvu.parl.gc.ca/Harmony/en/PowerBrowser/PowerBrowserV2/20240502/-1/41452 Time stamps: My address to the committee: 15:57:58 - 16:02:54 Discussions related to my address: 16:32:05 - 16:37:02 16:46:17 - 16:49:24 17:15:46 - 17:19:48 (As printed in Supply Professional Magazine, February 2024 - to see the original please click HERE.) During the COVID-19 pandemic, the term “supply chain resilience” became ubiquitous. People who had never heard of, or cared about, supply chains suddenly became aware of how quickly a system failure can impact the simplest aspects of life. Companies were willing to acknowledge that they “don’t know what they don’t know” about supply chains, because there was no shame in admitting to the same challenges as everyone else. While circumstances were obviously not beneficial, the increased awareness around supply chain risk and resilience was.

Why it matters

These problems impact more than just the supply and demand of materials, services, or resources. The interconnected nature of supply chains also impacts employment. Managing supply chains requires decentralized, distributed operations and decision making, which support and inform separate functions like marketing, sales, finance, engineering, R&D, service, and production. If your supply chain is impacted or stops, so too will these roles. If your supply chain is resilient, these functions (and your company) will benefit. Employment is an impact that passes beyond the factory walls into local and global economies. According to Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, as of 2020, $90.5 billion in wages came from manufacturing, which happened to be down from the previous year by $6.7 billion, and 93.2 per cent of these manufacturers have 99 employees or less. 6.2 per cent have 100 to 499 employees, and only 0.6 per cent have more than 500 employees. Total revenues for 2020 were $678.4 billion, down from $748.2 billion just a year before. As well, 4.5 per cent of our GDP comes from manufacturers. These numbers illustrate that nearly all of them are small to medium in size. Few companies in Canada’s manufacturing sector are large to global in size – but likely contribute disproportionately more to GDP than the majority of small companies. So making these small- and medium-sized manufacturers more resilient should be a concern. These firms are the least able to adapt quickly to changing business environments due to limited resources and capacity. The result is, they stagnate or fail. The “winners” are those that pivot faster than the competition, with the least increase in fixed or variable costs. In other words, it’s a competitive advantage to have supply chain resilience that’s effective and affordable within a business’s specific operating realities. Aren’t our larger manufacturers the best place to focus on resilience, due to their economic contributions? From my experience, in the long-term the answer is no. The reasons are simple. What happens when a major manufacturing firm, which generates such a large economic contribution, decides to pull up stakes, for any of a number of possible reasons? The results are devastating on local communities, and long-term. Furthermore, Canada’s manufacturing is predominantly low volume, high value/mix/customization goods. Unlike any volume manufacturing (think consumer goods), these products have their own supply chain challenges that are often overlooked by the volume-based best practices of the large manufacturing firms. The future landscape of Canada’s manufacturers includes far more small and medium firms and fewer large ones because needs will be decentralized, with local specializations and requirements. Redefining Canada’s place Geopolitically, the world is changing fast. In North America, a large portion of the population is retiring, and they are pulling in their own capital to fund it. This means declining capital for R&D, funding for new companies and other longer-term investments. Several parts of the world are entering a population implosion, meaning that political and trade challenges aside, some key supply partner nations will soon no longer be able to produce our goods competitively. We will return (more-or-less) to the pre-Second World War era where countries will survive or fail based on their own natural and internal resources, their abilities to process those resources, and their ability to produce the goods they need to maintain their living standards. In Canada, we have outsourced (or retired) most of our processing capability and knowledge. Now, the long-term survival of our nation’s independence falls on a rapid reacquisition and scaling of these capabilities. More broadly, finding effective solutions to climate change, poverty, and economic instability depends on the integrated system thinking inherent in supply chain resilience principles. Beyond re-shoring, we need a reindustrialization. We have the natural resources, but we must build on our processing capacity and make it resilient. Our small and medium manufacturers can be the foundation for this reindustrialization. And why not? Besides our natural resources, we are well positioned to do this with methods that are more sustainable and efficient than before. After all, cost effectiveness and sustainability are natural outputs of resilient supply chains. We will always need goods and resources. Our ability to produce them will depend on our supply chain resilience, or we will be at the mercy of someone else’s. Our small and medium manufacturers should be the foundation on which to secure our future prosperity. Why “Naviga”?

Recently, we announced that we have rebranded to Naviga Supply Chain. While most people can immediately understand our focus, we do get the question “why Naviga”? Simply put, Naviga means “to navigate”. And so, our focus, is to help firms navigate their supply chains in order to be able to see and anticipate the impact of strategic and tactical decisions. Not just any firms – Naviga is specifically focused on Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) Manufacturers. Why SME Manufacturers? Because they have the most complex, most variable, and most volatile supply chains anywhere. Low volume high value manufacturing environments are not static, they are fluid, highly dynamic, and come with challenges that are not fully addressed by conventional “best practices” developed in large scale manufacturing firms. Some of these challenges include:

The majority of Canada’s manufacturing fits into the SME category. This is why Naviga’s primary focus is the development of a supply chain resilience framework, built to recognize and accommodate the specific challenges of these manufacturers. Why a resilience framework? Because SME Manufacturers have highly variable supply chain challenges, with equally variable risks and threats to their operations. There is no “one size fits all” approach to identifying the best solutions. But a framework can bring forward an organized approach that considers all major elements of any supply chain as an integrated system. This allows any firm who uses the framework the autonomy to focus on those elements most relevant to their specific challenges, as well as solutions that fit in their specific business realities. And, they can leverage a greater understanding of the integration of those elements to arrive at solutions that benefit their supply chains overall. By far, the most requested support from our clients has been around improving resilience in their supply chains. Globally, manufacturing firms of all sizes are recognizing supply chain resilience as a top priority. Our work empowers SMEs them to see both risks and opportunities inherent in their existing supply chains in a quantitative fashion, and provides them with a means to prioritize and measure the cost/benefit relationship of solutions. Of course, all of this is done through a System Thinking approach, in that the outcomes must benefit the firm as a whole, not some small piece of it in isolation. The benefits of this approach are many:

Putting System Thinking to Work to Build Resilient Supply Chains for SMEs The Naviga team has been taking a System Thinking approach since we were founded in 2016. In addition, we have a specialized focus and understanding of low volume, high value/mix manufacturing. Applying this approach to supply chain resilience through a comprehensive framework is the logical next step for Naviga to support the manufacturing community. If you would like to find out more about how this could be applied to your company, feel free to reach out directly to Matt Weller. This car is “green” - Why context is key, especially when it comes to supply chain resilience10/25/2022

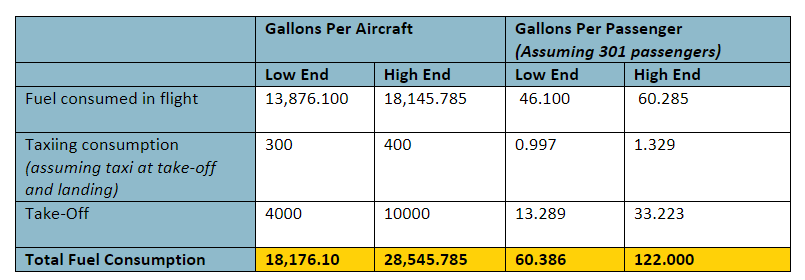

And not just literally green in colour! True, it’s a big old boat with a V-8, that gets roughly 19 miles per gallon, and it predates modern emissions systems. But, it’s more environmentally friendly than it first appears. I’ve owned this car for 26 years. Usually it gets a thumbs up, people smile and wave. Recently however it gets some comments like, “you shouldn’t be allowed to drive that, you’re killing the earth”. This was said by a proud Electric Vehicle owner who just got back from a vacation in the UK. So how can this car be “green”? The answer is simple, and it is the same answer that applies no matter if you’re talking about politics, the environment, or the many supply chain problems we have today: Context is everything! We are bombarded daily with sensational messaging that abandons context to manipulate emotional reactions, for anything ranging from political views to your next purchase of a good or service. No matter the subject, if you’re serious about making real results, details and context matter. I’ll give an example and show how it applies to supply chain. A basic example: My ’69 Chevy Impala has driven a total of 13,000 miles in the 26 years have owned it. That averages to 500 miles per year. Antique cars don’t get around much by modern driving standards! In 13,000 miles, my car has burned approximately 684 gallons of fuel in the name of my own enjoyment. The hobby of owning and maintaining this car not only brings me joy but also challenges engineering problem solving skills, sourcing skills, and forces learning new skills (such as welding). It helps me to relax and encourages me to take time to productively de-stress. Now let's look at how that compares to a vacation to the UK Boeing advertises that a 777 averages between 150-200 gallons during taxiing and 4,000 to 10,000 gallons during take off. On average, a 777 carries 301 passengers and burns 0.013 to 0.017 gallons per passenger per mile[1] Based on this, a rough (but not at all exact) understanding of fuel burned to take a flight to the UK for the sake of comparison, can be attained. The detailed math has been provided at the end but the chart below shows the summary data. Distance to UK (Toronto Pearson to London Heathrow) 7 hours 5 minutes, 5707 kilometers (converted to miles = 3546.165)[2] If I add up total consumption of fuel over the entire lifetime of my car (53 years, 133,000 miles averaging 19 mpg) including the first 20 years when it was a daily driver, it equals roughly 7,000 gallons, still less than half of a one-way trip to the UK by the lowest estimates! Without context, my car of course looks like it is causing more harm to the environment compared to a fully electric car. However, when looking closer at fuel consumption of our recreational habits, a one-way trip across the ocean caused approximately 27 times as much impact in just a few hours (41 times if you rely on the high estimates) than my car has in 26 years. But wait! You’re comparing personal use with an entire aircraft you might say. Well, the data from above shows us that a single passenger accounts for between 60 and 122 gallons one way. By the time my friend makes his return trip, he’s burned the equivalent amount of fuel that my vintage car would use in 4.5 years on the low side, 9.3 years on the high side! However, if you consider how many planes are in the air at any given time, vs vintage cars on the road, the CO2 contribution of old cars becomes so miniscule that it is statistically irrelevant to the global (or local) problem. To be clear, I am not suggesting people should not travel. Nor am I suggesting they shouldn’t feel good about owning an EV. But I am suggesting everyone should look at their own individual lifestyles and decide what impact they are having, what benefits they receive from it, and what is the compounded effect. There are no one-size fits all solutions, context is key and without seeing the whole picture we are basing judgements on assumptions that are likely to be false. Why is Context Important for Supply Chain Resiliency? We are living in a world of endless disruption, challenges, and problems. And just like environmental and political concerns, the problems are very real but many solutions are often “shell games” of selectively reporting and concealing different aspects of the problem, and almost always with a spin. So how can you build a supply chain that is agile and resilient? With context! Dr. W Edwards Deming, a world-renowned engineer and statistician, would refer to this as appreciating and understanding the system in which your business operates. There are two principles of systems I want to highlight:

It is important to note that tampering is the inevitable result of making changes - no matter how big, small, or well intentioned - while not understanding the system fully and quantitatively. And two concepts that go along with these are:

For any business with a supply chain (which is pretty much any business!), you cannot understand your own system from within. It requires persons and/or data from outside your system to detail out the realities, unbiased by internal interpretations, goals, preferences/beliefs, or politics. It also requires a structured approach to evaluate those realities that can stand up to scrutiny. It requires specific investigation into the business since while fundamentally all businesses have the same overall challenges (profit/loss, labour/productivity, markets) the details (context!) are what makes one fail and the other succeed. No two companies have the same details. The variables in every system must be understood in detail to provide proper context. Without this level of attention, things get worse. Today’s supply chains are a global example of this in real time where solutions are attempted in isolation rather than considering the entire system. We are making public policies, trade decisions, staging political campaigns, throwing money at some areas while ignoring others, and we still try to do this from an isolated solution-selling point of view, not from a data-based system solution point of view. Locally, at the individual business level, (particularly Small and Medium Enterprises) surviving the day takes priority. So, in turn, as an overall system, things get worse at the local level, which in turn drives global system errors, which feeds back to the local level in a runaway feedback loop. We can’t “tamper” our way out of these challenges. And we can’t improve any system that we do not see or understand. When you see social media posts especially about supply chain that say “25% of companies have X supply chain problem” or “40% of manufacturers think Y” as an example, you know immediately it’s misleading if it doesn’t specify: what companies, in what industry, making what products, based on what commodities, in what geographies, under what trade agreements, based on what data, from what source, collected for what purpose, funded by who, etc. Because it all matters. Context is King. Beware any person or product that evades providing specific (data based) context to anything, as they are not contributing to the solution. The only way out of our biggest business challenges are straight through them, navigated by context. Further Reading

Math calculations explained Fuel consumed in flight (gallons per passenger) Low end: 0.013 x 3546.165 = 46.100 High end: 0.017 x 3546.165 = 60.285 Taxiing consumption (gallons per passenger) Low end: 150 x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 300 ÷ 301 passengers = 0.997 High end: 200 x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 400 ÷ 301 passengers = 1.329 Take off (gallons per passenger) Low end: 4000 ÷ 301 passengers = 13.289 High end: 10,000 ÷ 301 passengers = 33.223 Total consumption (gallons per passenger) Low end: Flight (46.100) + Taxiing (0.997) + Take off (13.289) = 60.386 High end: Flight (60.285) + Taxiing (1.329) + Take off (33.223) = 122.000 Total fuel consumed by the aircraft (gallons): Flight Low end: 0.013 x 3546.165 = 46.100 gallons per passenger x 301 passengers = 13,876.100 High end: 0.017 x 3546.165 = 60.285 gallons per passenger x 301 passengers = 18,145.785 Taxiing (gallons) Low end: 150 gallons x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 300 gallons High end: 200 gallons x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 400 gallons Take off (gallons) Low end: 4000 gallons High end: 10,000 gallons Total fuel consumed by aircraft (gallons) = Low end: Flight (13,876.100) + Taxiing (300) + Take off (4000) = 18,176.10 High end: Flight (18,145.785) + Taxiing (400) + Take off (10,000) = 28,545.785 Footnotes

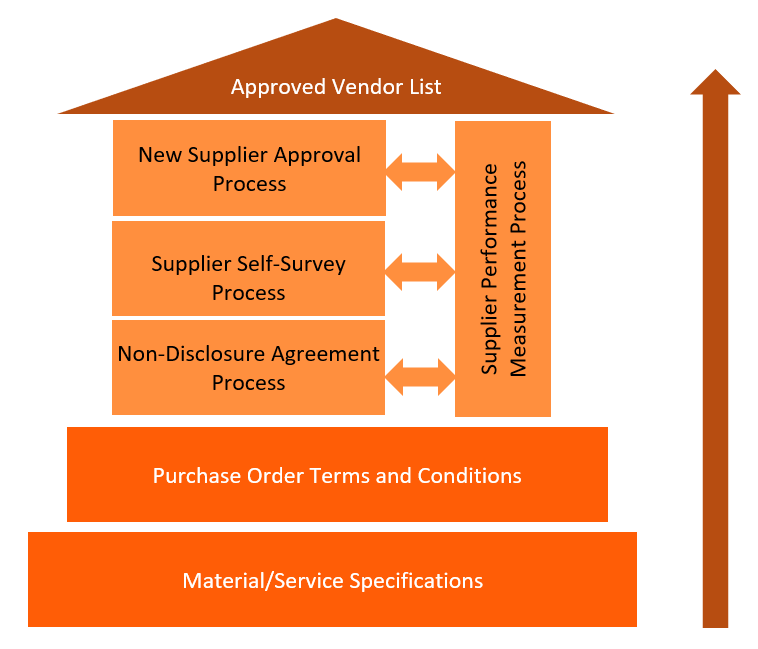

[1] How Much Fuel Does a Plane Use? Executive Flyers, August 15, 2022 [2] https://www.airportdistancecalculator.com/flight-yyz-to-lhr.html [3] https://youtu.be/M2Sw751ghao Over the past 6 years, the Berlin KraftWorks team has been working with manufacturers to help them achieve scaled operations. When Matt Weller and Peter Heuss formed Berlin KraftWorks (BKW), their goal was to make modern manufacturing understandable and accessible, while also working to build a stronger network between local manufacturers here in Waterloo Region. They did this by aligning engineering and supply chain which optimized solutions from initial product design through to delivery to customers. However, in 2020 things began to change. Our clients were facing continuous supply chain challenges, partly due to the pandemic, and they needed help. We were hearing from more Small and Medium sized Manufacturers (SMEs) who needed help navigating the complexities and risks of modern supply chains. While the pandemic has receded, the need has only continued to grow. At the same time, Peter Heuss was getting ready to start his retirement. BKW would never be the same without Peter and this was an opportunity for Matt to reassess what our clients needed from us.  We are pleased to announce that Berlin KraftWorks is now, Naviga Supply Chain. We still believe in a system thinking approach and use that methodology with our clients, however our focus is now on supply chain resiliency. The Naviga team is made up of supply chain and operations professionals with decades of hands-on experience in manufacturing, giving us insight to the unique supply chain challenges of SME’s here in Canada. We are looking forward to helping our clients prepare for resiliency by building supply chains that are competitive and easier to navigate. Do you have any questions about Naviga Supply Chain? We’d love to hear from you. Please reach out to Matt Weller via email, [email protected]. This is the 5th and final installment in my series concerned with Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch. Through the previous 4 installments, I’ve talked about key foundational elements for any supply chain – regardless of the product. The capstone that brings it all together is Supplier Management, and I will describe my own approach in this final article. Please note, in order to keep this down to a reasonable read, I will speak in general terms. For a detailed explanation of any of these elements, please contact me and I will be happy to expand on specific elements with examples. Supplier Management: The Approved Vendor List Process The Foundation I refer to this entire process as the Approved Vendor List (AVL). The AVL is the output, but the underlying processes are required to identify reliable sources of supply and manage a supply base capable of delivering goods and services at the right price, quality, quantity, and date. The core components of the AVL are required to make the list functional. There are four (4) core processes and two foundational components which underlie this (and other processes), without which the ability to manage suppliers is compromised. Foundation Stones: Material/Service Specifications and Purchase Order Terms and Conditions Material / Service Specification The Bill of Materials (BOM) dictates the materials/service specifications and is part of the design intent. It is the foundation for all supplier management processes, and the last word in what is required in combination with individual material specifications for items in the BOM. To better understand the Material/Service Specifications, please refer to part four of this series. Purchase Order Terms and Conditions Purchase Order Terms and Conditions are critical to any supplier interaction. From the beginning of an interaction, they set the tone of the relationship, define who is responsible for what, establish how quality will be determined and measured, and finally they stipulate how disputes will be resolved. Failure to clearly communicate with the supplier is by far the #1 root cause of poor supplier performance complaints that I have seen over the years. Ultimately, you own responsibility for communication as part of design responsibility, but also as part of your business strategy. It is unwise, and unfair, to rely on suppliers to assume they know what you need. The Four Core Processes Non-Disclosure Agreement In order to ensure an adequate level of due diligence, a non-disclosure agreement should be signed prior to the exchange of any sensitive information with any party. You will want to find out key things related to your supplier’s capabilities, status, and stability. You will also need to share with them key details about your own operations for context. It is best if this agreement is mutual. Please Note - While NDAs are used globally, they are not necessarily valid in some countries! Do your homework to ensure your confidentiality agreements will be recognized in foreign jurisdictions. Supplier Self-Survey In order to have a baseline set of data upon which to evaluate any new supplier, a Supplier Self-Survey should be completed. (Please contact me directly if you would like some examples around how to create a supplier self-survey). I use this survey to reveal summary process capability, financial status, and organizational fit information pertinent to making a reliable determination about a supplier's suitability to provide any product or service. This document should be reviewed in a cross-functional manner with input from Finance, along with any other functional group which is involved in defining the product or service requirement such as Engineering and Customer Service. Don’t overlook Quality personnel, their input is critical. In many situations QA staff will champion this part of the process. Under no circumstances should this survey be used as a replacement for an initial supplier visit/site audit. It is critically important to see your supplier’s operations firsthand, as this always reveals information you would not otherwise know. Most often, it reveals information that is beneficial to everyone involved as it may uncover previously unknown opportunities. A site visit with a completed self-survey in hand, helps to guide and verify the supplier’s suitability. New Supplier Approval Process This is required to validate new sources of supply, and ensure new suppliers can meet the needs of the organization reliably and in a repeatable fashion. This process depends on the Supplier Self-Survey as a data collection framework, as well as the NDA Process as a means to ensure due diligence in sharing sensitive information. You will need to consider how to “try out” this potential new supplier, with a trial, samples, or first-off production. There are various ways this can be done as it depends on many factors, your specific requirements should be considered to determine the best practice here. If the trials go well, the same group that considered the survey details should reconvene to determine if this supplier should be placed on the AVL. Its best to add a supplier on a conditional basis, such as a set period of time or the successful completion of a set volume of production before they are on the list unconditionally. Keep in mind that the AVL will be used by Engineers and Designers as the first consideration of available resources as they do their work, and Sourcing professionals will use this list to validate if their needs can be first met within their existing network (best case) or if work must be done to find a new supplier. From an R&D standpoint, it can be a waste to spend days searching for suppliers if the existing supply base is capable to meet the requirements. As such, this list needs to be maintained as a living document. Business decisions will rely on it, and supplier status can change drastically from approved to disqualified in short order. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 – The Bill of Materials: The Journey is at Least as Important as the Destination |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed