|

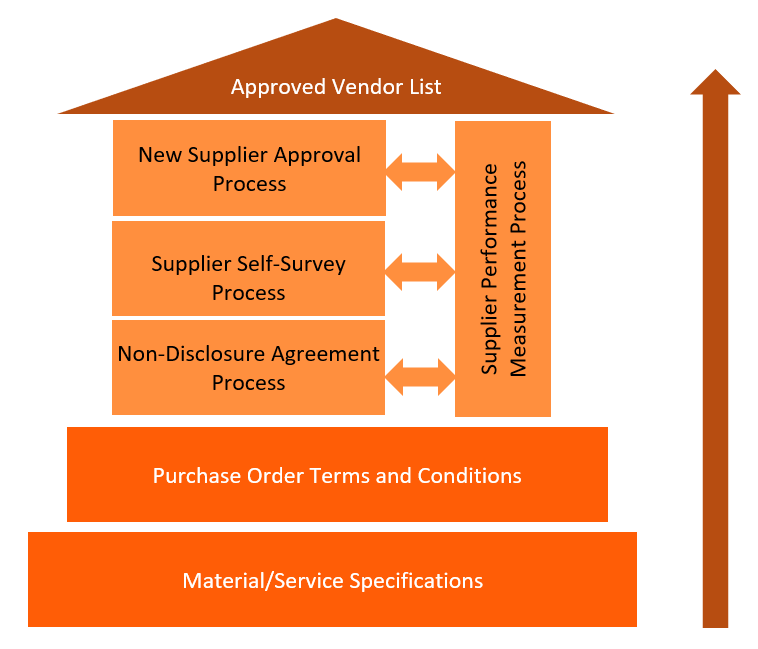

This is the 5th and final installment in my series concerned with Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch. Through the previous 4 installments, I’ve talked about key foundational elements for any supply chain – regardless of the product. The capstone that brings it all together is Supplier Management, and I will describe my own approach in this final article. Please note, in order to keep this down to a reasonable read, I will speak in general terms. For a detailed explanation of any of these elements, please contact me and I will be happy to expand on specific elements with examples. Supplier Management: The Approved Vendor List Process The Foundation I refer to this entire process as the Approved Vendor List (AVL). The AVL is the output, but the underlying processes are required to identify reliable sources of supply and manage a supply base capable of delivering goods and services at the right price, quality, quantity, and date. The core components of the AVL are required to make the list functional. There are four (4) core processes and two foundational components which underlie this (and other processes), without which the ability to manage suppliers is compromised. Foundation Stones: Material/Service Specifications and Purchase Order Terms and Conditions Material / Service Specification The Bill of Materials (BOM) dictates the materials/service specifications and is part of the design intent. It is the foundation for all supplier management processes, and the last word in what is required in combination with individual material specifications for items in the BOM. To better understand the Material/Service Specifications, please refer to part four of this series. Purchase Order Terms and Conditions Purchase Order Terms and Conditions are critical to any supplier interaction. From the beginning of an interaction, they set the tone of the relationship, define who is responsible for what, establish how quality will be determined and measured, and finally they stipulate how disputes will be resolved. Failure to clearly communicate with the supplier is by far the #1 root cause of poor supplier performance complaints that I have seen over the years. Ultimately, you own responsibility for communication as part of design responsibility, but also as part of your business strategy. It is unwise, and unfair, to rely on suppliers to assume they know what you need. The Four Core Processes Non-Disclosure Agreement In order to ensure an adequate level of due diligence, a non-disclosure agreement should be signed prior to the exchange of any sensitive information with any party. You will want to find out key things related to your supplier’s capabilities, status, and stability. You will also need to share with them key details about your own operations for context. It is best if this agreement is mutual. Please Note - While NDAs are used globally, they are not necessarily valid in some countries! Do your homework to ensure your confidentiality agreements will be recognized in foreign jurisdictions. Supplier Self-Survey In order to have a baseline set of data upon which to evaluate any new supplier, a Supplier Self-Survey should be completed. (Please contact me directly if you would like some examples around how to create a supplier self-survey). I use this survey to reveal summary process capability, financial status, and organizational fit information pertinent to making a reliable determination about a supplier's suitability to provide any product or service. This document should be reviewed in a cross-functional manner with input from Finance, along with any other functional group which is involved in defining the product or service requirement such as Engineering and Customer Service. Don’t overlook Quality personnel, their input is critical. In many situations QA staff will champion this part of the process. Under no circumstances should this survey be used as a replacement for an initial supplier visit/site audit. It is critically important to see your supplier’s operations firsthand, as this always reveals information you would not otherwise know. Most often, it reveals information that is beneficial to everyone involved as it may uncover previously unknown opportunities. A site visit with a completed self-survey in hand, helps to guide and verify the supplier’s suitability. New Supplier Approval Process This is required to validate new sources of supply, and ensure new suppliers can meet the needs of the organization reliably and in a repeatable fashion. This process depends on the Supplier Self-Survey as a data collection framework, as well as the NDA Process as a means to ensure due diligence in sharing sensitive information. You will need to consider how to “try out” this potential new supplier, with a trial, samples, or first-off production. There are various ways this can be done as it depends on many factors, your specific requirements should be considered to determine the best practice here. If the trials go well, the same group that considered the survey details should reconvene to determine if this supplier should be placed on the AVL. Its best to add a supplier on a conditional basis, such as a set period of time or the successful completion of a set volume of production before they are on the list unconditionally. Keep in mind that the AVL will be used by Engineers and Designers as the first consideration of available resources as they do their work, and Sourcing professionals will use this list to validate if their needs can be first met within their existing network (best case) or if work must be done to find a new supplier. From an R&D standpoint, it can be a waste to spend days searching for suppliers if the existing supply base is capable to meet the requirements. As such, this list needs to be maintained as a living document. Business decisions will rely on it, and supplier status can change drastically from approved to disqualified in short order. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

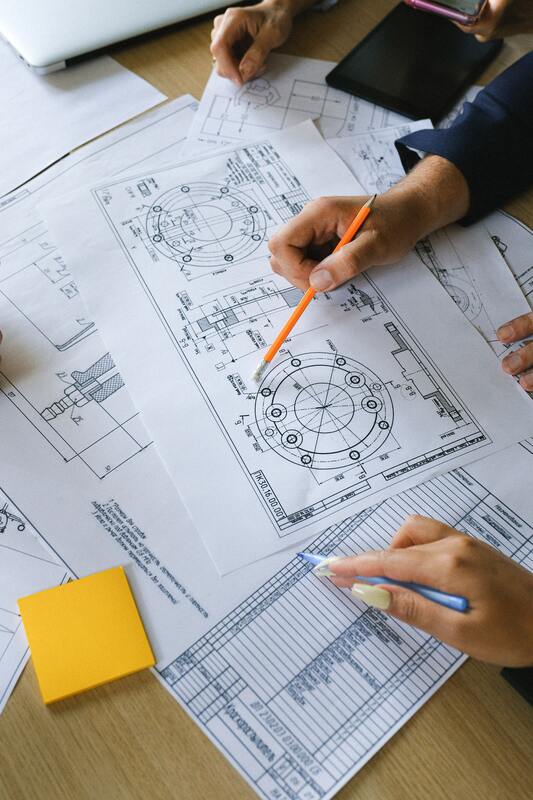

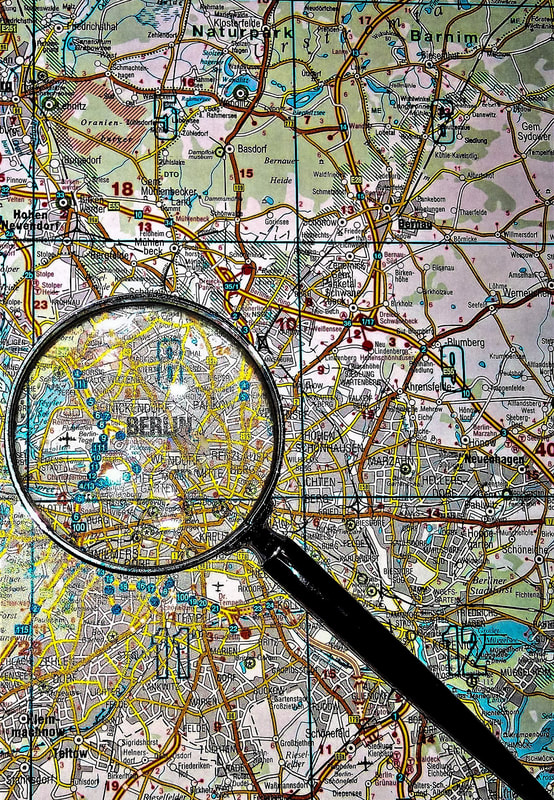

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 – The Bill of Materials: The Journey is at Least as Important as the Destination In part 3 of this series, I discussed the planning hierarchy and how it can be adapted and used to create both a model through which to structure a supply chain (from both a strategic and executional perspective) as well as how it can be used as a lens to prioritize supply chain activities. Its critically important to have a set of rules or standards around which to compare and contrast strategy and execution. It is the Bill of Materials (or BOM as it is commonly referred to) that sets these standards. Many early-stage companies believe that supply chain begins once the BOM has been established, but this is a critical error. This is because the BOM doesn’t exist on its own. While the BOM informs supply chain of required materials and specifications, it is the supply chain that informs the BOM itself about what it can viably include. Therefore the BOM serves as the bonding point between two iterative functions: supply chain and product design. However, it is important to remember that the BOM as a completed data set is merely the result, and a snapshot in the evolution of that data. It will continue to evolve with the product. The journey to get to a completed BOM is at least as important, if not more important, as the BOM itself. Avoiding unobtanium Throughout my career I have seen failed product launches due entirely to designs that have not been informed by critical factors such as: supply availability of specific parts, international trade considerations (logistics, regulations, customs, etc.), and even social/political/economic factors of either the regions of the materials supplied or the regions where the product is being shipped. That’s because a BOM can only represent what goes into something, it cannot represent why or how. It is in fact the journey of iterative exploration of different materials, parts, suppliers, manufacturing methods and supply regions that informs as to the viability of any design consideration, and invariably will influence design towards the lowest risk options while maintaining the overall functional requirements of the design. Sometimes functional requirements cannot be supported after supply chain research, and this is better to discover early on (as opposed to pre-production). Baking-in materials or processes into a design that are impossible to buy or support reliably (humorously referred to as “unobtanium”) is a recipe for failure. Often however, the design viability can be improved drastically with early iterative interactions between design and supply chain. Part specifications Perhaps the most important part of the process is the creation of specifications for each and every item which will eventually be included in a BOM. This is as equally important to supply chains as they are to product design. In Design, all the components must act together as a system, ultimately focused on the form, fit, and functional requirements of the end product as dictated by the business case. For every item in the BOM, specific requirements must be spelled out including not just dimensions, and tolerances, but also (for commercially available components) approved brands, models, and manufacturer specifications. Even more important still, is the understanding of why all those specifications are required, relative to the greater system in which they are to become a part of. It goes farther to support strategic management of materials and supply strategies, also referred to as “Plan for Every Part”. These specifications are always arrived at through continual trial and error, testing and refinement. In supply chain, its impossible to source products, evaluate potential suppliers, or manage inventories or demands, without specifications. It is those specifications which will measure what will be acceptable, and what will not. For this reason, sourcing is often executed after much or all the BOM has been established. However, this is far too late and ensures delays, and risks failure in the development process. Instead, supply chain must work hand-in-hand with engineering through the design process, considering possible sources, and manufacturers in concert with the engineering effort. Supply chain also needs to engage possible suppliers for advice (particularly for any item made to specification – but not exclusively since “off the shelf” products must also be fully specified and understood) to understand manufacturing limitations and opportunities for efficiency. All of this must be gathered and relayed back to engineering as meaningful data, and engineering can then reciprocate with design iterations that are viable from a supply chain point of view. The importance of revision control Of course, as the design is evolving a tremendous amount of time and effort will be lost if there is no mechanism in place to track the evolution as well as documenting every change and the specific reasons for the change. For engineering, this is the process where all the learning and intelligence (IP) around the product is developed and retained. So it is also true with supply chain, as supplier and component strategies depend on understanding the intimate details (and challenges) of every specific part. Supply chain is sometimes affected by revisions, and other times is the cause of revisions (supply problems OR possibilities of better items/technologies become available) but a complete knowledge of the evolution is required to strategize and optimize the supply chain as well as manage day-to-day operations once in production. Shared ownership is no ownership While the BOM is the connective tissue between engineering and supply chain, responsibility for the BOM, its revisions and specifications lie squarely with engineering. Why? Because the BOM is the stated design intent of all components relative to the end product (or in other words, relative to the system they must work together in). Design intent cannot be shared jointly by supply chain and engineering, nor should it ever be. Likewise, responsibility for supplier relationships, strategies and sourcing methods lie squarely with supply chain and cannot be shared with engineering. These are, in effect the “design intent” elements of the supply chain system and production execution that must produce those specifications dictated by engineering. While both design intent and supply/execution strategy inform and influence each other, anything less than a clear delineation of ownership will make everything run amuck in short order. When creating a supply chain from scratch, the finished BOM is only a snapshot in time. The knowledge generation, supply strategies, and overall viability of the supply chain is made or broken by the journey to the BOM, not the BOM itself. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 5 - Supplier Management Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch: Part 3 – The Planning Hierarchy: unlocking the path forward7/27/2021

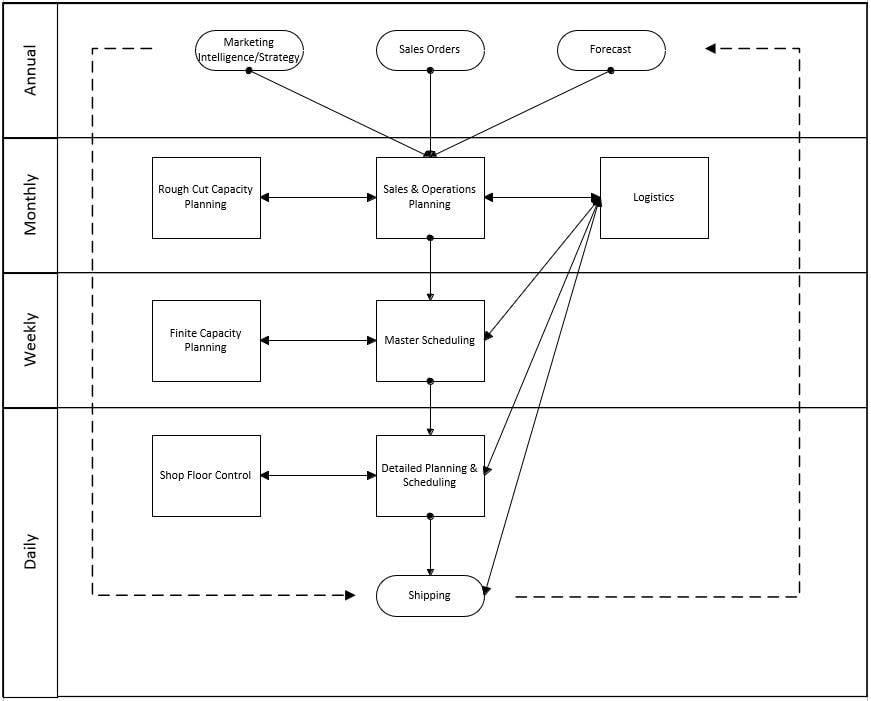

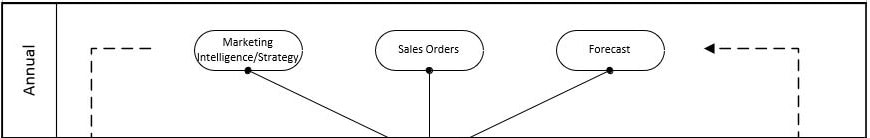

In part 2 of this series, I talked about the chaos of the very early stages of any company, or product and how to approach that chaos as both infinite complexity but also infinite opportunity. Since its neither practical nor productive to try to create a product or supply chain system that is all things, to all customers, all at once, we’ve got to apply some boundaries to the complexity and opportunity. We need to focus – on the data, activities and risk/reward opportunities that will best bring us toward our goals. Preferably with the least amount of time, effort, and cost wasted as possible. The planning hierarchy is the structure and the lens through which to achieve this. And, as a structure it allows you to apply a System Thinking approach to planning your product and your supply chain. The structure is applicable to any company that produces a physical product, regardless of if they are a start-up, or a well established multi-national giant. The key however, is in how to apply it. To understand that you have to have a relentless focus on your customer, and your business case to provide value to that customer as well as to the business (if the business cannot generate value, it won’t be a business for very long!) The hierarchy is the roadmap, how you decide to get there will determine your operations strategy and the overall success, profitability, and sustainability of your company. The further we go down the planning hierarchy, the more detailed and short term our decisions (and repercussions) become. But each level needs to be aligned to supporting the business case above all else. A typical planning hierarchy (applicable to any manufacturing company) appears as follows: Applying this framework to a start-up In a start-up (as with any company) things need to be considered from two views simultaneously from day one: how will decisions impact the project/company today, and how decisions impact the project/company tomorrow and beyond. Building a brand-new supply chain from scratch is no different, since project or business decisions made today can have implications and costs that the company will have to bear for weeks, months or possibly for the entire product life-cycle including cost, risk, effort to produce, and agility to react quickly to changing market conditions. For start-ups it can be difficult, if not impossible, to know all that you need to know for success. This is the complexity or chaos I’ve mentioned previously. In order to overcome this, most start-ups will forgo any consideration of supply chain and focus on marketing and product engineering while leaving supply chain to a later date when there aren’t so many variables. In most cases, these firms will invest time and money into developing a product, only to have to do much or all of it a second time to produce a product that can actually be viable for manufacturing and supply chain, that will actually generate a profit, and will deliver measurable value to the customer. This time lag can be deadly to early-stage companies, who will either run out of funding or simply be beaten to market by a better organized competitor. Instead, I argue that the planning hierarchy can be adopted to meet and overcome these complexities during development, not after. And the process will result in a purpose-designed supply chain that develops concurrently with the product. Let’s walk though some ways to apply this. Business Level Considerations (Annual Outlook/Consideration) At the top of the planning hierarchy, your supply chain must consider the business case. The business case is the anchor. If this isn’t solid, anything tied to it will be no better. At the top of the planning hierarchy are the long-term and broad concerns to be responded to. Long term considerations:

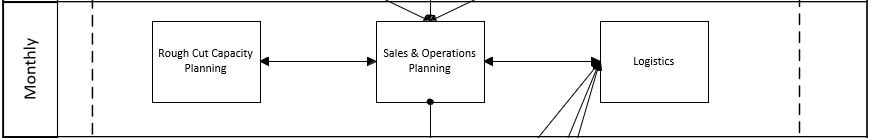

While nobody can expect to understand these elements fully (especially sales forecasts) for a new product or for an early-stage firm, it’s worth mentioning that they need to be understood as well as they can be and be constantly challenged when new information is available. The business case grows and matures in this way, and the complexity of the supporting planning hierarchy will grow and mature accordingly to support it. In the planning hierarchy, these are usually annual considerations since to change direction in any of these elements requires a major reworking of all supporting systems. It is also important to note that this is why supporting systems should be no more complex then necessary, for maximum agility in times of crisis. Operations Considerations (Shorter term, typically monthly) Once the business case is identified, vetted and validated, product development can begin in earnest. There may already be some napkin sketches or even conceptual models, but now all that must be tempered with the requirements of the business case. The development will look up to the business case and also any available feedback from potential customers or markets as a guide. Operational considerations:

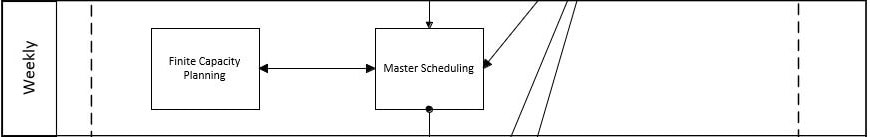

Inputs and outputs here can, and will, change more frequently than the business case, especially in product development because new information is learned as the development cycle progresses. In a production environment, this is a monthly exercise. But in a start-up, it should be considered at any decision affecting the product development and design. A criticism I have often heard is “why spend that time for things that are only conceptual, isn’t that waste?” The answer is a firm no. All of this work, if documented, becomes your supply chain knowledge base specific to your product and it will inform both your design and your supply chain strategies as you go. It will orient your products and your operations towards viability at first, and competitive advantage over the long haul by steering you clear of pitfalls and avoidable challenges. Detailed Production Considerations (Weekly) In production, this level of detail is a weekly review cycle, but in a start-up, it becomes something completely different. Start-ups that are just developing their products aren’t engaged in capacity planning or master scheduling of production. Instead, consideration needs to be given to how, at a detailed level, your product will be produced based on the development done to date. Detailed production considerations:

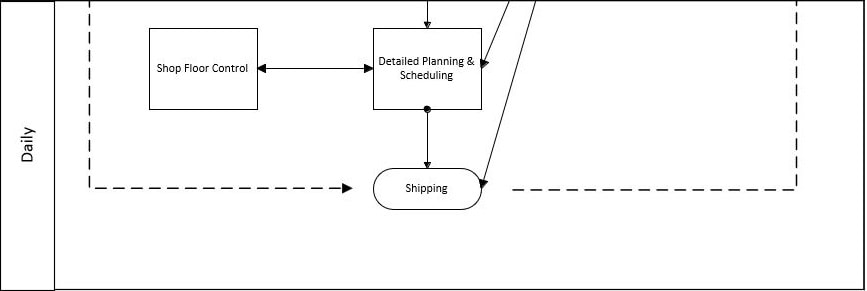

Figuring these out post-development is far too late, and will force a re-do of much (or all) of the development cycle to re-align with the realities of supply and resources, before any real production can happen. The opportunity here for a start-up, is to really research what resources are available and weigh cost against value. This is where you can build your database of who is out there, and what they can offer and share that with the development team. Its also a good opportunity to build relationships and vet ideas with potential manufacturing or supply partners who are subject matter experts. This is where the heart of your new supply chain – data guided by knowledge, will start to grow. Daily Execution Considerations At the bottom of the hierarchy is all the detailed day-to-day considerations of producing your product. In production, this would include daily activities around the shop floor – scheduling machines and people, daily material consumption and replenishment, as well as shipping and receiving (both your finished goods to customers, but also incoming supply of materials) to name just a few things. Ultimately, the details at this level will determine your profit margin, your quality, and your ability to satisfy the customer. In many ways the work done at higher levels will frame how effective work at this level can be. For a start-up, this can be applied as additional detail to the elements already described when considering specific aspects of the design and how it will be produced in scale. Considerations for daily operations:

Bringing it All Together This is just the beginning. There is more that can be done to apply this hierarchy to a start-up, in order to streamline development and build a viable supply chain concurrently. Much more in fact than I can touch on in a short blog. But hopefully this illustrates how this framework can serve to cut through complexity and unlimited variability inherent in start-ups with a repeatable, scalable supply chain structure that can grow with the firm and guide the product development towards successful execution, by designing and developing with the end in mind the whole time. The effectiveness of the end result be governed by your supply chain, for better or worse. They key to remember is that it is never too early to start this process. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 - The Bill of Materials - The Journey is At Least As Important as the Destination Part 5 - Supplier Management In part 1 of this series I discussed some fundamental ideas and approaches required to start from scratch and build a supply chain system. If you take those to heart, you will find that you are immediately confronted with incredible, unlimited complexity and variability around what to do next. I call this chaos, that which is unknown, impossible to know, and virtually impossible to plan for. In an early-stage company, or at the earliest stages of any product development, chaos is all that exists. Chaos can present itself to organizations as:

We are told that we need to plan, set rules, buy technology, and invest capital with the promise that we will eliminate chaos. But how do you eliminate that which is unknown and impossible to know? Embrace the chaos We are taught to view chaos as a bad thing. I argue that creativity in its purist form is chaos, and no innovation or leap of progress can be made without it. A music composer takes infinite complexity, the unlimited chaos of sounds, colours, and emotions and blends them into a masterpiece. Successful businesses don’t spend much time trying to avoid chaos, instead they manage those things that are within their control and build processes that can respond ever quicker to changing complexities and those things they can’t control. Life is chaos, to attempt to live life chaos free is futile. If you are at an early-stage and building a supply chain from scratch, then you owe your very existence to chaos. Your new firm or product idea was born because existing companies or products failed to respond to some changing need, some complexity, some type of chaos. It is up to us to embrace and harness the power of chaos. A balance between order and chaos In part 1, I mentioned that you need to focus on those things which you can control. Those controls are required to ensure that your firm operates consistently, predictably, with known costs, benefits, and measurable progress for any given activity. In supply chain, this means that there is a hierarchy or universal organization of elements which must exist (and must exist as an interactive system) before any of those elements can function well. Back in the day, we referred to it as “the planning hierarchy”. My former professor and mentor, the late Lloyd M. Clive (co-author of the seminal book “Introduction to Materials Management”) used to tell me “tattoo that hierarchy onto your brain, and you will be able to navigate any conceivable supply chain challenge". After 20 years of testing that assertion, I can confirm that he was exactly right. However, and this is critical, this structured approach should not be applied to prevent chaos. Instead, consider that it is required to bring your focus where it needs to be to consistently and predictably manage what is known while also harnessing chaos by providing a system flexible enough to learn and adapt on a dime. Processes for process’s sake – an unmeasurable waste I have seen countless firms build process upon process, implement technology upon technology, in order to “improve performance” without consideration of the overall business case, or without a system thinking approach. This approach is flawed. The inevitable outcome is a strict, inflexible set of policies and processes which do the opposite of perform, they absorb capital and time (an unrenewable resource) and most often end up existing for the sake of existence. We’ve all just witnessed a great example in real life with young start-ups pivoting to fill PPE needs faster than the well-established firms could react, and go on to prevail in delivering value to their customers. Start-ups are full of chaos (unlimited complexity), while mature firms are full of order (constraints applied to reduce complexity). But its chaos that demands order to constantly evolve. The planning hierarchy need not be complicated, in fact its better if it's not. It should be continuously measured and reviewed against the business case, to ensure that it is controlling that which can be controlled, predictably and reliably. And the business case should be continually measured against performance to the customer needs. Anything beyond that is waste. Early-stage firms will require only basic elements in their planning hierarchy, and if any of them become more effort to manage than the benefit they provide, you have to consider that it may be going too far. Consider Continuous improvement, a well-known (and important) part of effectively managing process. But if there is a shift in the business case, or processes are no longer supporting the business case (ex. dominant focus on local-level performance metrics instead of system-level) firms are at risk of creating more waste in continuous improvement instead of improving performance. Dr Russel L. Ackoff, a pioneer in System Thinking once said “Continuous improvement isn’t nearly as important as discontinuous improvement.” And indeed, he was right. Discontinuous improvement is chaos. It is step-function change, as opposed to gradual ongoing improvement. It’s also the ability to pivot and adapt quickly when conditions or requirements change unpredictably, or when the customer demands it. For early-stage companies, the adoption of process controls and best practices is not nearly as important as adaptation of principles to the specific situation of the firm or the product. Putting it together I usually tell those who are building a supply chain from scratch, to embrace the chaos but keep that seatbelt on. Process and a hierarchy are required to reduce the chaos to manageable terms, but the key is to adapt these to the firm's needs, not to adapt the firm to the process needs. If viewed with a system thinking mindset, the task of balancing chaos with order will be dictated by how well the firm understands and delivers to its customer. Chaos allows the firm to be creative, and well-developed order allows the firm to quickly adapt to changing conditions with greater speed, ease, and repeatability However, it’s critical to remember that the customer is the most important part and process must never consume more than the value it delivers. In my next post, I’ll explore the planning hierarchy in detail and how it becomes the foundation for any firm’s supply chain (and operations), and how it can be adapted to early-stage firms. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 - The Bill of Materials - The Journey is At Least As Important as the Destination Part 5 - Supplier Management “How do I establish a supply chain? What are the most important elements of a supply chain for a start-up or early stage company? How can I build supply partners when I don’t have any volume yet?” These are the most common questions that I hear from start-ups and early stage companies, and they are excellent questions! How do you create a supply chain when you have very few people, minimal resources, low volume, and next to no budget? In Canada more than 90% of our manufacturing firms are Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), and that number is growing rapidly. Unfortunately, most supply chain discussions and methodology are focused on improving already existing operations for larger firms, often with more capital and higher volumes of production than the majority of SMEs. As an entrepreneur, this is incredibly frustrating. From a supply chain perspective, a business that bases its revenue on producing tens and hundreds of something can be harder to manage than continuously improving an established supply chain that has scaled to mass-production due to the extreme variables in cost, time, customer and supplier terms, etc. Although, with the onset of COVID-19, even the well-established methods being put to the test. Shifting consumer values and economic conditions are changing the way companies produce - high-volume, low mix/value production is giving way to low volume high mix/customization/value products and services. Here in Canada, we are well positioned to be global masters of low volume, high value products. Products in this category include items such as mission critical medical devices, scientific equipment, and consumer goods designed for a market where longevity, quality, and sustainability are prioritized over cheap and disposable products. However, this model is infinitely more complex with far more variability than traditional high-volume manufacturing. Building a supply chain from nothing is an entirely different science than anything that applies to the mass-manufacturing world. Today I’ll give you my 4 best tips for establishing your supply chain. 1) Focus on What You Can Control If you find yourself in a company that’s establishing a supply chain for the first time, then odds are that you have some sort of business education or career experience. You may have formal supply chain training, as I do. If that experience has been focused on well-established supply chains, you may find starting from zero to be an overwhelming proposition. Worse, if you are rigid in “how it should be done”, you may find that it’s almost easier to forget what you know than to try to determine how to apply it to completely different circumstances. Traditional standards and best practices from large or well-established firms and/or mass manufacturers are often just not practical for early stage or low volume/high value producers. Today with COVID-19, business conditions can change hourly (forget daily) and that level of variability can’t be met with incomparable past experience. So, the first step is to shift to a mindset that doesn’t try to control variables that we can’t (with incomparable experience) and instead focus only on that which we can control. We do this through system thinking and evidence-based decision making. 2) Understand that Supply Chain is not a thing or a standard, it’s a result that is dynamic and constantly changing. Supply Chain is a result, not an independent function or activity. It is the result of several cross-functional business processes and how well (or not) they work together. You can’t build or refine a supply chain as an individual entity; you must build better business processes and integrate them with a system view (focused on the business case and delivering customer value - or not producing anything customers aren't willing to pay for) which will result in better supply chain performance including resilience and agility. That’s not to say that supply chain will “build itself”, but rather what you do build as supply chain can only be as good as the business processes to which its connected, and all of it only as good as the whole-system view and value chain. This is why Supply Chain is a strategic function, despite common ideas that it’s a transactional or administrative function. Supply Chain is the ultimate measure of your overall business system in real time, and your focus on delivering value to your customer. 3) Supply chain begins long before you have a physical product. I’ve often seen firms get a working prototype and announce that they are now ready to consider supply chain and manufacturing, only to find out that much of the work they have done must be undone and redone (at the expense of time and cost) because what they developed is not manufacturable or able to be supported with supply in the volumes, costs or quality required. The resulting delay to market or unplanned capital requirements can be deadly. In reality, your supply chain considerations begin sometime after someone has a product idea but before its first iteration is scribbled on a napkin. You need to have input from professionals within the various disciplines that are collectively called “supply chain”. As a new product idea iterates from vision, to napkin, to proof of concepts to pre-production prototypes, the supply chain iterates also and in parallel. To me, it can’t be anything other than a fully integrated development cycle. While the product designers, engineers, product managers, marketers and sales team are working to create a product that a customer is willing to pay for, supply chain folks (sourcing, purchasing, logistics, materials/inventory/production management) as well as potential suppliers (for individual products, or contract manufacturers) must weigh-in to advise what is possible to produce within the constraints of cost, materials availability (short and long term) lead time, as well as international trade concerns, shipping regulations, quality standards, etc. The supply chain begins as an evolution of an idea, grown by the acquisition and validation of information and resources that are ultimately tuned to the business case and customer demands. It identifies areas of risk, and often facilitates negotiation and trade-offs between different areas/interests in a firm to arrive at the best and most viable outcome from an execution point of view. If all the functions involved have done their due diligence along the way and validated customer needs against identified constraints of delivering those needs, the end result will a manufacturable product that provides value the customer is willing to pay for. It is important to note that there are two customers to consider - the external customer who buys, and the internal customer who depends on information. Access to these professional skill sets can be tricky for early firms, in many cases it can be far more economical to hire professionals on an as-needed basis so long as you understand how to properly integrate those resources within a system thinking framework that supports your business case. 4) Remember Everything You’ve Learned but Keep an Open Mind While in step 1 above it may have felt like it would be better to forget everything you know, in this step you may realize that you have the opportunity to apply portions of your past experience that (with testing, modification, or improvement) may be adaptable to this new product or business case. And other portions may be completely inappropriate to the specific business case and should be left behind. But until you are ready and willing to throw it all out in favour of a wide-open mind, then you are subject to the same old enemies of progress: “I’ve always done it this way”, and you cannot see the opportunities that lie hidden in the knowledge gaps that everyone has, which are uncovered through collaboration. This shift in mindset is the single biggest factor that will make or break a young company or product, because it limits one’s ability to adapt old knowledge with the present conditions, and create new knowledge and experience that is highly relevant to the firm right now and down the road. While it sounds trivial, its actually harder than one may think. In a future blog, I’ll discuss the most important functional elements required to establish a supply chain system from scratch, in any firm. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 - The Bill of Materials - The Journey is At Least As Important as the Destination Part 5 - Supplier Management With COVID-19 restrictions closing most offices, many of us had a few months trying to navigate working from home. By now, some of you may have returned to your place of business, and while I am sure it has changed quite a bit to the way things were prior to COVID-19, it is different than working from home.

I am not going to talk about the technical challenges or the furniture and space required of setting up a home office. There have been many great articles written about this and chances are you read them when you first started working from home. I want to discuss how working from home has been for you, what challenges it has brought up, and possible ways of creating a better experience for you now and in the future. Let’s start with one of the obvious differences: Distractions. I am home. My wife or partner is working on his/her own project and occasionally needs my input or wants to share his/her thoughts. What is the BIG deal, right? What about having your kids run around? They are likely home as well and expect to be entertained. Throw in a dog or a cat, and calls from friends and family since they are not working and seek your attention. And of course, one of the biggest distractions – ME. When I’m at home in my own space, “I get to make tea or coffee whenever I feel like it, have a snack here and there, make lunch, watch a bit of TV (just one Netflix episode…), or listen to music or the radio. Oh yes, then there are all these other chores I have on my to-do-list. Why not do some of them since I feel like it and taking care of the garbage only takes a few minutes anyway, right?” In other words, working from home can create the perfect storm when it comes to distractions. It can be difficult to get any work done. Are you someone that is getting easily distracted and pulled away to other tasks and opportunities? Or maybe it is the other way around for you? Let’s take a look at that. While you are typically focused and disciplined at work, meetings and interruptions are frequent. Perhaps working from home is a blessing in disguise. “Finally, I can concentrate on my work without anything or anyone getting in my way. Hey, I might even work 10-hour days. My plate is so full that I could use that extra time to clean up my backlog.” Speaking for myself I can get so focused that all of a sudden, I missed a meal or two, being far away in la-la land and hardly approachable. Being in the zone and deeply concentrating can provide a great amount of satisfaction, however, over a period of time there is a good chance that fatigue and tiredness sets in, if not even burnout. Finding Balance Working from home can be a wonderful thing for both, you and your employer If you can find a way to balance both work and your personal life. Getting sufficient work done to keep your project moving forward, to show good performance, and taking time for yourself, your family, and your friends. Here some ideas you can think about. Answer these questions for yourself. Make a plan, and do your best to stick to it. Present your plan to your loved ones and/or negotiate with them to create a win-win for everyone.

What are your biggest challenges around working from home and how you have been able to make this work for you? I’d love to hear your thoughts or questions, feel free to reach out through the Contact form. Efficient Product Development is Driven by a System Approach That Continually Considers Value12/17/2019

Nearly all product development is a multi-disciplinary effort, usually with tight constraints on time, cost and function. But most engineering groups tend to design in isolation, where even the different engineering disciplines don’t interact, let alone considering supply chain, manufacturing, service, test etc… The risk is a design that doesn’t meet the business goals and needs to be reworked or adversely affects the company’s performance. I’ve learned this hard way in the past, having to re-design mechanical systems, for example, when they wouldn’t work with what the electrical engineers designed.

There are two principles that will help develop better products, quicker – value analysis (a part of lean and value stream theory) and systems design. Every process is made up of a series of steps or tasks. These tasks may not be linear, there may be a complex set of interactions required, but they always share the same basic structure. Every task includes a set of inputs, has a set of required outputs, has stakeholders who use those outputs, and is done under a set of constraints. The outputs should be based entirely on the value they deliver. The end goal is always to produce a product that meets the company’s goals as outlined in their business case. If the output of any task doesn’t contribute to those business goals, it’s waste. If the output has to be reworked because it doesn’t work with some other part of the design, it’s also waste. The inputs are where many design processes slip. I think everyone will agree that every part in a design is somehow affected by the other parts. It could be as simple as a bracket holding a PCB or as complicated as a motion control system controlling the movement of mechanical components driven by remote user input. The key to effective design is to consider those interactions from the start of design. System thinking is a way of looking at the inter-relationships of parts once they have been combined into a system. A portion of a design may seem appropriate on its own, but when taken in context with the entire system may fail. For example:

System Design is the application of systems theory to product development, taking a multi-disciplinary approach to design and implementation. It’s not a new concept, but it’s one that will save a lot of design time and produce a better design. The key to planning and executing the design is to first to consider the value each task creates. The three primary aspects of value are:

If we understand what value each task is to deliver, we can better understand what needs to be designed, and more importantly what is not required. And that helps determine what inputs we need to carry out that design. Those inputs will typically be from multiple sources including the design specification, outputs from preceding tasks, input from concurrent tasks, and some additional design knowledge and information. If we continually look at how each task is effected by previous tasks and how it is effected by and affects concurrent tasks, we can complete each task in a way the develops the most value for the overall system. By considering the entire system when planning each design task, and the value that task is generating, we can be more effective, producing better designs with less waste. At BKW we're very proud to have our Value Stream Mapping projects guided by Brian Watson. Brian is a supply chain system thinking expert, and he has spent his entire career helping firms across various sectors improve their performance. Brian spent 21 years in manufacturing, enjoying much success improving the performance of the firms he managed. For 18 years, Brian was a Professor of Supply Chain & Operations Management at Conestoga College. Since 2017, Brian has been the Director of the Magna Centre for Supply Chain Excellence at Conestoga.

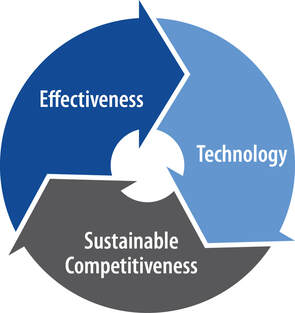

Through his role with Conestoga College, Brian has been able to share his knowledge and increase awareness of the importance of system thinking in improving firm competitiveness in this dynamically complex global economy. Recently, he authored a whitepaper focused on Canada’s productivity and how system thinking enables businesses to strive for sustainable competitiveness. The following is an excerpt from the whitepaper, Addressing Canada’s Productivity Challenge: Sustainable Competitiveness Through Integrative Supply Chain System Thinking (May 2018). Canada’s economy lags behind many other nations in terms of productivity. It is projected that Canada’s productivity growth rate will be slower than many of its peers over the next thirty years. Addressing Canada’s productivity is a dynamically complex challenge, impacted by international, national and organizational factors. While governments hammer out trade agreements, tax and business policy regimes, there is much that individual organizations can and must do to address productivity improvement. The predominant argument put forward to address productivity improvement is that of investment in technology. While investment in technology is necessary, it is not sufficient in addressing Canada’s productivity challenge. Many SME’s do not have the resources or skills to invest in technology, while other firms invest in technology without truly understanding its impact, often resulting in unintended negative consequences. Organizations must first place their efforts and resources on improving system effectiveness in delivering ever increasing customer value. Only then should investment in technology occur. Effectiveness first, then selective investment in technology where appropriate, in a never-ending process of innovation, knowledge creation, continuous improvement and value creation. Doing so generates much needed financial and human capital and improves operational and financial performance, allowing the organization to leap ahead of the competition and establish sustainable competitiveness in the process. To achieve this, a transformation in thinking and behaviour is required. This paper will identify two key areas requiring the immediate attention of executives and senior management across all organizations. The first is the development of mission critical integrative supply chain system thinking competencies in their organizations. Integrative supply chain system thinking marries training in effective supply chain management with system thinking, then applies these in addressing the productivity challenge. In the process key competencies are developed, necessary for improving an organization’s effectiveness in delivering ever increasing customer value and improved productivity in today’s (and tomorrow’s) dynamically complex global economy. Of note, in 2016 the World Economic Forum (WEF) identified the top ten skills required by organizations needed to thrive in the fourth industrial revolution.* Those top ten skills include;

Integrative supply chain system thinking competencies, when developed as outlined in this paper, and in concert with effective leadership, embodies all of these skills. The second key area requiring immediate attention is that of organizational culture. An organization’s culture must be one that encourages collaboration, risk taking, is focused on customer value creation, adopts continuous improvement as foundational to its strategic approach, and regards all employees and key supply chain partners as critical to the creation of innovative new knowledge. Developing such a culture requires organizational leadership that values and adopts such principles and approaches in the day to day managing of the firm. Unfortunately, such leadership is at odds with traditional cost-focused management culture found in many organizations today yet is absolutely essential to achieving sustainable competitiveness in today’s (and tomorrow’s) dynamically complex global economy. World leading productivity, and with that true sustainable competitiveness in the global economy, comes through the effective application and leveraging of all of an organization’s resources, not just technology. This is true for organizations in all sectors of the economy. It takes skilled supply chain specialists trained in system thinking to effectively leverage all resources including technology; integrating, coordinating, and optimizing them to achieve world leading productivity and system performance. It also takes a leadership culture that fosters an environment in which knowledge creation, innovation, and continuous improvement toward true sustainable competitiveness can flourish. This paper reviews the work of a number of key thought leaders in defining integrative supply chain system thinking. Additionally, a case involving a manufacturing firm is outlined throughout the paper in an effort to better understand the importance of integrative supply chain system thinking to improving organizational effectiveness. Improving productivity in Canada is an urgent matter that must be addressed by governments, business, and education systems alike. Unless taken seriously and accompanied by specific action, Canada’s productivity, and with it our competitiveness and standard of living will continue to fall behind. This paper is a call to action to all organizational leaders to address the productivity challenge. It is also a review of what needs to be in place for improved productivity and sustainable competitiveness to be achieved. If you are an organizational leader charged with the responsibility to improve your organization’s/supply chain’s performance then I encourage you to continue reading. If you would like to read the full whitepaper, please click here. *The Future of Jobs, Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution Report, World Economic Forum, January 2016, as summarized in, Alex Gray, The 10 skills you need to thrive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, January 19, 2016, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-10-skills-you-need-to-thrive-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution World Economic Forum, Retrieved February 26, 2018. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed