|

(As printed in Supply Professional Magazine, February 2024 - to see the original please click HERE.) During the COVID-19 pandemic, the term “supply chain resilience” became ubiquitous. People who had never heard of, or cared about, supply chains suddenly became aware of how quickly a system failure can impact the simplest aspects of life. Companies were willing to acknowledge that they “don’t know what they don’t know” about supply chains, because there was no shame in admitting to the same challenges as everyone else. While circumstances were obviously not beneficial, the increased awareness around supply chain risk and resilience was.

Why it matters

These problems impact more than just the supply and demand of materials, services, or resources. The interconnected nature of supply chains also impacts employment. Managing supply chains requires decentralized, distributed operations and decision making, which support and inform separate functions like marketing, sales, finance, engineering, R&D, service, and production. If your supply chain is impacted or stops, so too will these roles. If your supply chain is resilient, these functions (and your company) will benefit. Employment is an impact that passes beyond the factory walls into local and global economies. According to Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, as of 2020, $90.5 billion in wages came from manufacturing, which happened to be down from the previous year by $6.7 billion, and 93.2 per cent of these manufacturers have 99 employees or less. 6.2 per cent have 100 to 499 employees, and only 0.6 per cent have more than 500 employees. Total revenues for 2020 were $678.4 billion, down from $748.2 billion just a year before. As well, 4.5 per cent of our GDP comes from manufacturers. These numbers illustrate that nearly all of them are small to medium in size. Few companies in Canada’s manufacturing sector are large to global in size – but likely contribute disproportionately more to GDP than the majority of small companies. So making these small- and medium-sized manufacturers more resilient should be a concern. These firms are the least able to adapt quickly to changing business environments due to limited resources and capacity. The result is, they stagnate or fail. The “winners” are those that pivot faster than the competition, with the least increase in fixed or variable costs. In other words, it’s a competitive advantage to have supply chain resilience that’s effective and affordable within a business’s specific operating realities. Aren’t our larger manufacturers the best place to focus on resilience, due to their economic contributions? From my experience, in the long-term the answer is no. The reasons are simple. What happens when a major manufacturing firm, which generates such a large economic contribution, decides to pull up stakes, for any of a number of possible reasons? The results are devastating on local communities, and long-term. Furthermore, Canada’s manufacturing is predominantly low volume, high value/mix/customization goods. Unlike any volume manufacturing (think consumer goods), these products have their own supply chain challenges that are often overlooked by the volume-based best practices of the large manufacturing firms. The future landscape of Canada’s manufacturers includes far more small and medium firms and fewer large ones because needs will be decentralized, with local specializations and requirements. Redefining Canada’s place Geopolitically, the world is changing fast. In North America, a large portion of the population is retiring, and they are pulling in their own capital to fund it. This means declining capital for R&D, funding for new companies and other longer-term investments. Several parts of the world are entering a population implosion, meaning that political and trade challenges aside, some key supply partner nations will soon no longer be able to produce our goods competitively. We will return (more-or-less) to the pre-Second World War era where countries will survive or fail based on their own natural and internal resources, their abilities to process those resources, and their ability to produce the goods they need to maintain their living standards. In Canada, we have outsourced (or retired) most of our processing capability and knowledge. Now, the long-term survival of our nation’s independence falls on a rapid reacquisition and scaling of these capabilities. More broadly, finding effective solutions to climate change, poverty, and economic instability depends on the integrated system thinking inherent in supply chain resilience principles. Beyond re-shoring, we need a reindustrialization. We have the natural resources, but we must build on our processing capacity and make it resilient. Our small and medium manufacturers can be the foundation for this reindustrialization. And why not? Besides our natural resources, we are well positioned to do this with methods that are more sustainable and efficient than before. After all, cost effectiveness and sustainability are natural outputs of resilient supply chains. We will always need goods and resources. Our ability to produce them will depend on our supply chain resilience, or we will be at the mercy of someone else’s. Our small and medium manufacturers should be the foundation on which to secure our future prosperity. This car is “green” - Why context is key, especially when it comes to supply chain resilience10/25/2022

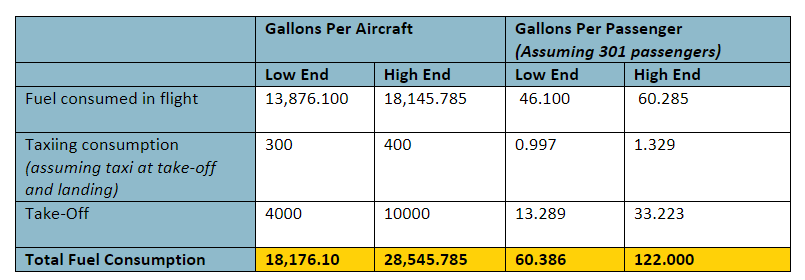

And not just literally green in colour! True, it’s a big old boat with a V-8, that gets roughly 19 miles per gallon, and it predates modern emissions systems. But, it’s more environmentally friendly than it first appears. I’ve owned this car for 26 years. Usually it gets a thumbs up, people smile and wave. Recently however it gets some comments like, “you shouldn’t be allowed to drive that, you’re killing the earth”. This was said by a proud Electric Vehicle owner who just got back from a vacation in the UK. So how can this car be “green”? The answer is simple, and it is the same answer that applies no matter if you’re talking about politics, the environment, or the many supply chain problems we have today: Context is everything! We are bombarded daily with sensational messaging that abandons context to manipulate emotional reactions, for anything ranging from political views to your next purchase of a good or service. No matter the subject, if you’re serious about making real results, details and context matter. I’ll give an example and show how it applies to supply chain. A basic example: My ’69 Chevy Impala has driven a total of 13,000 miles in the 26 years have owned it. That averages to 500 miles per year. Antique cars don’t get around much by modern driving standards! In 13,000 miles, my car has burned approximately 684 gallons of fuel in the name of my own enjoyment. The hobby of owning and maintaining this car not only brings me joy but also challenges engineering problem solving skills, sourcing skills, and forces learning new skills (such as welding). It helps me to relax and encourages me to take time to productively de-stress. Now let's look at how that compares to a vacation to the UK Boeing advertises that a 777 averages between 150-200 gallons during taxiing and 4,000 to 10,000 gallons during take off. On average, a 777 carries 301 passengers and burns 0.013 to 0.017 gallons per passenger per mile[1] Based on this, a rough (but not at all exact) understanding of fuel burned to take a flight to the UK for the sake of comparison, can be attained. The detailed math has been provided at the end but the chart below shows the summary data. Distance to UK (Toronto Pearson to London Heathrow) 7 hours 5 minutes, 5707 kilometers (converted to miles = 3546.165)[2] If I add up total consumption of fuel over the entire lifetime of my car (53 years, 133,000 miles averaging 19 mpg) including the first 20 years when it was a daily driver, it equals roughly 7,000 gallons, still less than half of a one-way trip to the UK by the lowest estimates! Without context, my car of course looks like it is causing more harm to the environment compared to a fully electric car. However, when looking closer at fuel consumption of our recreational habits, a one-way trip across the ocean caused approximately 27 times as much impact in just a few hours (41 times if you rely on the high estimates) than my car has in 26 years. But wait! You’re comparing personal use with an entire aircraft you might say. Well, the data from above shows us that a single passenger accounts for between 60 and 122 gallons one way. By the time my friend makes his return trip, he’s burned the equivalent amount of fuel that my vintage car would use in 4.5 years on the low side, 9.3 years on the high side! However, if you consider how many planes are in the air at any given time, vs vintage cars on the road, the CO2 contribution of old cars becomes so miniscule that it is statistically irrelevant to the global (or local) problem. To be clear, I am not suggesting people should not travel. Nor am I suggesting they shouldn’t feel good about owning an EV. But I am suggesting everyone should look at their own individual lifestyles and decide what impact they are having, what benefits they receive from it, and what is the compounded effect. There are no one-size fits all solutions, context is key and without seeing the whole picture we are basing judgements on assumptions that are likely to be false. Why is Context Important for Supply Chain Resiliency? We are living in a world of endless disruption, challenges, and problems. And just like environmental and political concerns, the problems are very real but many solutions are often “shell games” of selectively reporting and concealing different aspects of the problem, and almost always with a spin. So how can you build a supply chain that is agile and resilient? With context! Dr. W Edwards Deming, a world-renowned engineer and statistician, would refer to this as appreciating and understanding the system in which your business operates. There are two principles of systems I want to highlight:

It is important to note that tampering is the inevitable result of making changes - no matter how big, small, or well intentioned - while not understanding the system fully and quantitatively. And two concepts that go along with these are:

For any business with a supply chain (which is pretty much any business!), you cannot understand your own system from within. It requires persons and/or data from outside your system to detail out the realities, unbiased by internal interpretations, goals, preferences/beliefs, or politics. It also requires a structured approach to evaluate those realities that can stand up to scrutiny. It requires specific investigation into the business since while fundamentally all businesses have the same overall challenges (profit/loss, labour/productivity, markets) the details (context!) are what makes one fail and the other succeed. No two companies have the same details. The variables in every system must be understood in detail to provide proper context. Without this level of attention, things get worse. Today’s supply chains are a global example of this in real time where solutions are attempted in isolation rather than considering the entire system. We are making public policies, trade decisions, staging political campaigns, throwing money at some areas while ignoring others, and we still try to do this from an isolated solution-selling point of view, not from a data-based system solution point of view. Locally, at the individual business level, (particularly Small and Medium Enterprises) surviving the day takes priority. So, in turn, as an overall system, things get worse at the local level, which in turn drives global system errors, which feeds back to the local level in a runaway feedback loop. We can’t “tamper” our way out of these challenges. And we can’t improve any system that we do not see or understand. When you see social media posts especially about supply chain that say “25% of companies have X supply chain problem” or “40% of manufacturers think Y” as an example, you know immediately it’s misleading if it doesn’t specify: what companies, in what industry, making what products, based on what commodities, in what geographies, under what trade agreements, based on what data, from what source, collected for what purpose, funded by who, etc. Because it all matters. Context is King. Beware any person or product that evades providing specific (data based) context to anything, as they are not contributing to the solution. The only way out of our biggest business challenges are straight through them, navigated by context. Further Reading

Math calculations explained Fuel consumed in flight (gallons per passenger) Low end: 0.013 x 3546.165 = 46.100 High end: 0.017 x 3546.165 = 60.285 Taxiing consumption (gallons per passenger) Low end: 150 x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 300 ÷ 301 passengers = 0.997 High end: 200 x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 400 ÷ 301 passengers = 1.329 Take off (gallons per passenger) Low end: 4000 ÷ 301 passengers = 13.289 High end: 10,000 ÷ 301 passengers = 33.223 Total consumption (gallons per passenger) Low end: Flight (46.100) + Taxiing (0.997) + Take off (13.289) = 60.386 High end: Flight (60.285) + Taxiing (1.329) + Take off (33.223) = 122.000 Total fuel consumed by the aircraft (gallons): Flight Low end: 0.013 x 3546.165 = 46.100 gallons per passenger x 301 passengers = 13,876.100 High end: 0.017 x 3546.165 = 60.285 gallons per passenger x 301 passengers = 18,145.785 Taxiing (gallons) Low end: 150 gallons x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 300 gallons High end: 200 gallons x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 400 gallons Take off (gallons) Low end: 4000 gallons High end: 10,000 gallons Total fuel consumed by aircraft (gallons) = Low end: Flight (13,876.100) + Taxiing (300) + Take off (4000) = 18,176.10 High end: Flight (18,145.785) + Taxiing (400) + Take off (10,000) = 28,545.785 Footnotes

[1] How Much Fuel Does a Plane Use? Executive Flyers, August 15, 2022 [2] https://www.airportdistancecalculator.com/flight-yyz-to-lhr.html [3] https://youtu.be/M2Sw751ghao |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed