|

Matt Weller Founder, Naviga Supply Chain Related links: Parliament recommendation #1: National Reindustrialization Strategy Parliament recommendation #2: Realign investment and build executional knowledge Parliament recommendation #3: Create an active, connected ecosystem for SME Manufacturers Recently, I was invited by our Parliaments’ Standing Committee on International Trade to talk about Canadian businesses in supply chains and global markets. On April 30th I had the opportunity to discuss the challenges that face our small and medium manufacturers, and why it is vital to our long-term economic future that we work to support and grow these companies.

Key takeaways include:

I offered three (3) solutions that I will expand on in future posts:

It was a privilege to participate in our Parliamentary Process! Full committee meeting here (static at start is momentary): https://parlvu.parl.gc.ca/Harmony/en/PowerBrowser/PowerBrowserV2/20240502/-1/41452 Time stamps: My address to the committee: 15:57:58 - 16:02:54 Discussions related to my address: 16:32:05 - 16:37:02 16:46:17 - 16:49:24 17:15:46 - 17:19:48 Why “Naviga”?

Recently, we announced that we have rebranded to Naviga Supply Chain. While most people can immediately understand our focus, we do get the question “why Naviga”? Simply put, Naviga means “to navigate”. And so, our focus, is to help firms navigate their supply chains in order to be able to see and anticipate the impact of strategic and tactical decisions. Not just any firms – Naviga is specifically focused on Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) Manufacturers. Why SME Manufacturers? Because they have the most complex, most variable, and most volatile supply chains anywhere. Low volume high value manufacturing environments are not static, they are fluid, highly dynamic, and come with challenges that are not fully addressed by conventional “best practices” developed in large scale manufacturing firms. Some of these challenges include:

The majority of Canada’s manufacturing fits into the SME category. This is why Naviga’s primary focus is the development of a supply chain resilience framework, built to recognize and accommodate the specific challenges of these manufacturers. Why a resilience framework? Because SME Manufacturers have highly variable supply chain challenges, with equally variable risks and threats to their operations. There is no “one size fits all” approach to identifying the best solutions. But a framework can bring forward an organized approach that considers all major elements of any supply chain as an integrated system. This allows any firm who uses the framework the autonomy to focus on those elements most relevant to their specific challenges, as well as solutions that fit in their specific business realities. And, they can leverage a greater understanding of the integration of those elements to arrive at solutions that benefit their supply chains overall. By far, the most requested support from our clients has been around improving resilience in their supply chains. Globally, manufacturing firms of all sizes are recognizing supply chain resilience as a top priority. Our work empowers SMEs them to see both risks and opportunities inherent in their existing supply chains in a quantitative fashion, and provides them with a means to prioritize and measure the cost/benefit relationship of solutions. Of course, all of this is done through a System Thinking approach, in that the outcomes must benefit the firm as a whole, not some small piece of it in isolation. The benefits of this approach are many:

Putting System Thinking to Work to Build Resilient Supply Chains for SMEs The Naviga team has been taking a System Thinking approach since we were founded in 2016. In addition, we have a specialized focus and understanding of low volume, high value/mix manufacturing. Applying this approach to supply chain resilience through a comprehensive framework is the logical next step for Naviga to support the manufacturing community. If you would like to find out more about how this could be applied to your company, feel free to reach out directly to Matt Weller. This car is “green” - Why context is key, especially when it comes to supply chain resilience10/25/2022

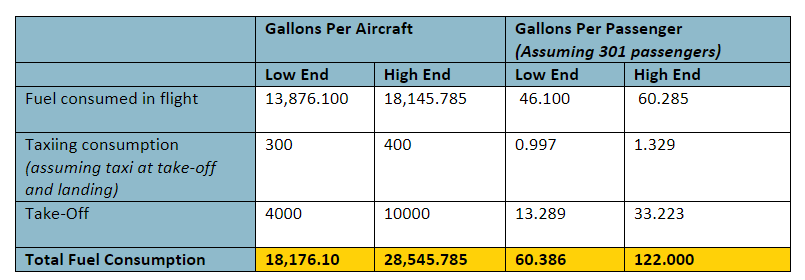

And not just literally green in colour! True, it’s a big old boat with a V-8, that gets roughly 19 miles per gallon, and it predates modern emissions systems. But, it’s more environmentally friendly than it first appears. I’ve owned this car for 26 years. Usually it gets a thumbs up, people smile and wave. Recently however it gets some comments like, “you shouldn’t be allowed to drive that, you’re killing the earth”. This was said by a proud Electric Vehicle owner who just got back from a vacation in the UK. So how can this car be “green”? The answer is simple, and it is the same answer that applies no matter if you’re talking about politics, the environment, or the many supply chain problems we have today: Context is everything! We are bombarded daily with sensational messaging that abandons context to manipulate emotional reactions, for anything ranging from political views to your next purchase of a good or service. No matter the subject, if you’re serious about making real results, details and context matter. I’ll give an example and show how it applies to supply chain. A basic example: My ’69 Chevy Impala has driven a total of 13,000 miles in the 26 years have owned it. That averages to 500 miles per year. Antique cars don’t get around much by modern driving standards! In 13,000 miles, my car has burned approximately 684 gallons of fuel in the name of my own enjoyment. The hobby of owning and maintaining this car not only brings me joy but also challenges engineering problem solving skills, sourcing skills, and forces learning new skills (such as welding). It helps me to relax and encourages me to take time to productively de-stress. Now let's look at how that compares to a vacation to the UK Boeing advertises that a 777 averages between 150-200 gallons during taxiing and 4,000 to 10,000 gallons during take off. On average, a 777 carries 301 passengers and burns 0.013 to 0.017 gallons per passenger per mile[1] Based on this, a rough (but not at all exact) understanding of fuel burned to take a flight to the UK for the sake of comparison, can be attained. The detailed math has been provided at the end but the chart below shows the summary data. Distance to UK (Toronto Pearson to London Heathrow) 7 hours 5 minutes, 5707 kilometers (converted to miles = 3546.165)[2] If I add up total consumption of fuel over the entire lifetime of my car (53 years, 133,000 miles averaging 19 mpg) including the first 20 years when it was a daily driver, it equals roughly 7,000 gallons, still less than half of a one-way trip to the UK by the lowest estimates! Without context, my car of course looks like it is causing more harm to the environment compared to a fully electric car. However, when looking closer at fuel consumption of our recreational habits, a one-way trip across the ocean caused approximately 27 times as much impact in just a few hours (41 times if you rely on the high estimates) than my car has in 26 years. But wait! You’re comparing personal use with an entire aircraft you might say. Well, the data from above shows us that a single passenger accounts for between 60 and 122 gallons one way. By the time my friend makes his return trip, he’s burned the equivalent amount of fuel that my vintage car would use in 4.5 years on the low side, 9.3 years on the high side! However, if you consider how many planes are in the air at any given time, vs vintage cars on the road, the CO2 contribution of old cars becomes so miniscule that it is statistically irrelevant to the global (or local) problem. To be clear, I am not suggesting people should not travel. Nor am I suggesting they shouldn’t feel good about owning an EV. But I am suggesting everyone should look at their own individual lifestyles and decide what impact they are having, what benefits they receive from it, and what is the compounded effect. There are no one-size fits all solutions, context is key and without seeing the whole picture we are basing judgements on assumptions that are likely to be false. Why is Context Important for Supply Chain Resiliency? We are living in a world of endless disruption, challenges, and problems. And just like environmental and political concerns, the problems are very real but many solutions are often “shell games” of selectively reporting and concealing different aspects of the problem, and almost always with a spin. So how can you build a supply chain that is agile and resilient? With context! Dr. W Edwards Deming, a world-renowned engineer and statistician, would refer to this as appreciating and understanding the system in which your business operates. There are two principles of systems I want to highlight:

It is important to note that tampering is the inevitable result of making changes - no matter how big, small, or well intentioned - while not understanding the system fully and quantitatively. And two concepts that go along with these are:

For any business with a supply chain (which is pretty much any business!), you cannot understand your own system from within. It requires persons and/or data from outside your system to detail out the realities, unbiased by internal interpretations, goals, preferences/beliefs, or politics. It also requires a structured approach to evaluate those realities that can stand up to scrutiny. It requires specific investigation into the business since while fundamentally all businesses have the same overall challenges (profit/loss, labour/productivity, markets) the details (context!) are what makes one fail and the other succeed. No two companies have the same details. The variables in every system must be understood in detail to provide proper context. Without this level of attention, things get worse. Today’s supply chains are a global example of this in real time where solutions are attempted in isolation rather than considering the entire system. We are making public policies, trade decisions, staging political campaigns, throwing money at some areas while ignoring others, and we still try to do this from an isolated solution-selling point of view, not from a data-based system solution point of view. Locally, at the individual business level, (particularly Small and Medium Enterprises) surviving the day takes priority. So, in turn, as an overall system, things get worse at the local level, which in turn drives global system errors, which feeds back to the local level in a runaway feedback loop. We can’t “tamper” our way out of these challenges. And we can’t improve any system that we do not see or understand. When you see social media posts especially about supply chain that say “25% of companies have X supply chain problem” or “40% of manufacturers think Y” as an example, you know immediately it’s misleading if it doesn’t specify: what companies, in what industry, making what products, based on what commodities, in what geographies, under what trade agreements, based on what data, from what source, collected for what purpose, funded by who, etc. Because it all matters. Context is King. Beware any person or product that evades providing specific (data based) context to anything, as they are not contributing to the solution. The only way out of our biggest business challenges are straight through them, navigated by context. Further Reading

Math calculations explained Fuel consumed in flight (gallons per passenger) Low end: 0.013 x 3546.165 = 46.100 High end: 0.017 x 3546.165 = 60.285 Taxiing consumption (gallons per passenger) Low end: 150 x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 300 ÷ 301 passengers = 0.997 High end: 200 x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 400 ÷ 301 passengers = 1.329 Take off (gallons per passenger) Low end: 4000 ÷ 301 passengers = 13.289 High end: 10,000 ÷ 301 passengers = 33.223 Total consumption (gallons per passenger) Low end: Flight (46.100) + Taxiing (0.997) + Take off (13.289) = 60.386 High end: Flight (60.285) + Taxiing (1.329) + Take off (33.223) = 122.000 Total fuel consumed by the aircraft (gallons): Flight Low end: 0.013 x 3546.165 = 46.100 gallons per passenger x 301 passengers = 13,876.100 High end: 0.017 x 3546.165 = 60.285 gallons per passenger x 301 passengers = 18,145.785 Taxiing (gallons) Low end: 150 gallons x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 300 gallons High end: 200 gallons x 2 (taxi at take off, and at landing) = 400 gallons Take off (gallons) Low end: 4000 gallons High end: 10,000 gallons Total fuel consumed by aircraft (gallons) = Low end: Flight (13,876.100) + Taxiing (300) + Take off (4000) = 18,176.10 High end: Flight (18,145.785) + Taxiing (400) + Take off (10,000) = 28,545.785 Footnotes

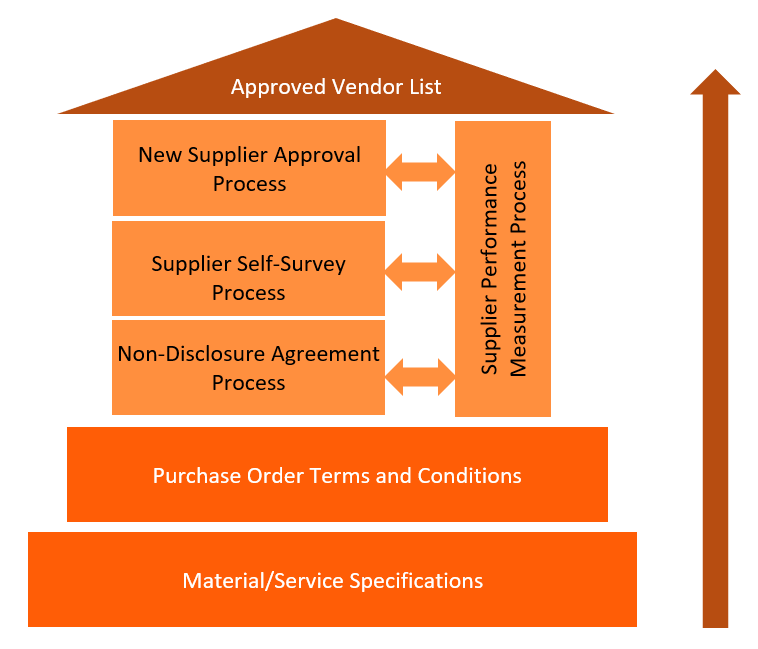

[1] How Much Fuel Does a Plane Use? Executive Flyers, August 15, 2022 [2] https://www.airportdistancecalculator.com/flight-yyz-to-lhr.html [3] https://youtu.be/M2Sw751ghao This is the 5th and final installment in my series concerned with Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch. Through the previous 4 installments, I’ve talked about key foundational elements for any supply chain – regardless of the product. The capstone that brings it all together is Supplier Management, and I will describe my own approach in this final article. Please note, in order to keep this down to a reasonable read, I will speak in general terms. For a detailed explanation of any of these elements, please contact me and I will be happy to expand on specific elements with examples. Supplier Management: The Approved Vendor List Process The Foundation I refer to this entire process as the Approved Vendor List (AVL). The AVL is the output, but the underlying processes are required to identify reliable sources of supply and manage a supply base capable of delivering goods and services at the right price, quality, quantity, and date. The core components of the AVL are required to make the list functional. There are four (4) core processes and two foundational components which underlie this (and other processes), without which the ability to manage suppliers is compromised. Foundation Stones: Material/Service Specifications and Purchase Order Terms and Conditions Material / Service Specification The Bill of Materials (BOM) dictates the materials/service specifications and is part of the design intent. It is the foundation for all supplier management processes, and the last word in what is required in combination with individual material specifications for items in the BOM. To better understand the Material/Service Specifications, please refer to part four of this series. Purchase Order Terms and Conditions Purchase Order Terms and Conditions are critical to any supplier interaction. From the beginning of an interaction, they set the tone of the relationship, define who is responsible for what, establish how quality will be determined and measured, and finally they stipulate how disputes will be resolved. Failure to clearly communicate with the supplier is by far the #1 root cause of poor supplier performance complaints that I have seen over the years. Ultimately, you own responsibility for communication as part of design responsibility, but also as part of your business strategy. It is unwise, and unfair, to rely on suppliers to assume they know what you need. The Four Core Processes Non-Disclosure Agreement In order to ensure an adequate level of due diligence, a non-disclosure agreement should be signed prior to the exchange of any sensitive information with any party. You will want to find out key things related to your supplier’s capabilities, status, and stability. You will also need to share with them key details about your own operations for context. It is best if this agreement is mutual. Please Note - While NDAs are used globally, they are not necessarily valid in some countries! Do your homework to ensure your confidentiality agreements will be recognized in foreign jurisdictions. Supplier Self-Survey In order to have a baseline set of data upon which to evaluate any new supplier, a Supplier Self-Survey should be completed. (Please contact me directly if you would like some examples around how to create a supplier self-survey). I use this survey to reveal summary process capability, financial status, and organizational fit information pertinent to making a reliable determination about a supplier's suitability to provide any product or service. This document should be reviewed in a cross-functional manner with input from Finance, along with any other functional group which is involved in defining the product or service requirement such as Engineering and Customer Service. Don’t overlook Quality personnel, their input is critical. In many situations QA staff will champion this part of the process. Under no circumstances should this survey be used as a replacement for an initial supplier visit/site audit. It is critically important to see your supplier’s operations firsthand, as this always reveals information you would not otherwise know. Most often, it reveals information that is beneficial to everyone involved as it may uncover previously unknown opportunities. A site visit with a completed self-survey in hand, helps to guide and verify the supplier’s suitability. New Supplier Approval Process This is required to validate new sources of supply, and ensure new suppliers can meet the needs of the organization reliably and in a repeatable fashion. This process depends on the Supplier Self-Survey as a data collection framework, as well as the NDA Process as a means to ensure due diligence in sharing sensitive information. You will need to consider how to “try out” this potential new supplier, with a trial, samples, or first-off production. There are various ways this can be done as it depends on many factors, your specific requirements should be considered to determine the best practice here. If the trials go well, the same group that considered the survey details should reconvene to determine if this supplier should be placed on the AVL. Its best to add a supplier on a conditional basis, such as a set period of time or the successful completion of a set volume of production before they are on the list unconditionally. Keep in mind that the AVL will be used by Engineers and Designers as the first consideration of available resources as they do their work, and Sourcing professionals will use this list to validate if their needs can be first met within their existing network (best case) or if work must be done to find a new supplier. From an R&D standpoint, it can be a waste to spend days searching for suppliers if the existing supply base is capable to meet the requirements. As such, this list needs to be maintained as a living document. Business decisions will rely on it, and supplier status can change drastically from approved to disqualified in short order. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 – The Bill of Materials: The Journey is at Least as Important as the Destination In part 3 of this series, I discussed the planning hierarchy and how it can be adapted and used to create both a model through which to structure a supply chain (from both a strategic and executional perspective) as well as how it can be used as a lens to prioritize supply chain activities. Its critically important to have a set of rules or standards around which to compare and contrast strategy and execution. It is the Bill of Materials (or BOM as it is commonly referred to) that sets these standards. Many early-stage companies believe that supply chain begins once the BOM has been established, but this is a critical error. This is because the BOM doesn’t exist on its own. While the BOM informs supply chain of required materials and specifications, it is the supply chain that informs the BOM itself about what it can viably include. Therefore the BOM serves as the bonding point between two iterative functions: supply chain and product design. However, it is important to remember that the BOM as a completed data set is merely the result, and a snapshot in the evolution of that data. It will continue to evolve with the product. The journey to get to a completed BOM is at least as important, if not more important, as the BOM itself. Avoiding unobtanium Throughout my career I have seen failed product launches due entirely to designs that have not been informed by critical factors such as: supply availability of specific parts, international trade considerations (logistics, regulations, customs, etc.), and even social/political/economic factors of either the regions of the materials supplied or the regions where the product is being shipped. That’s because a BOM can only represent what goes into something, it cannot represent why or how. It is in fact the journey of iterative exploration of different materials, parts, suppliers, manufacturing methods and supply regions that informs as to the viability of any design consideration, and invariably will influence design towards the lowest risk options while maintaining the overall functional requirements of the design. Sometimes functional requirements cannot be supported after supply chain research, and this is better to discover early on (as opposed to pre-production). Baking-in materials or processes into a design that are impossible to buy or support reliably (humorously referred to as “unobtanium”) is a recipe for failure. Often however, the design viability can be improved drastically with early iterative interactions between design and supply chain. Part specifications Perhaps the most important part of the process is the creation of specifications for each and every item which will eventually be included in a BOM. This is as equally important to supply chains as they are to product design. In Design, all the components must act together as a system, ultimately focused on the form, fit, and functional requirements of the end product as dictated by the business case. For every item in the BOM, specific requirements must be spelled out including not just dimensions, and tolerances, but also (for commercially available components) approved brands, models, and manufacturer specifications. Even more important still, is the understanding of why all those specifications are required, relative to the greater system in which they are to become a part of. It goes farther to support strategic management of materials and supply strategies, also referred to as “Plan for Every Part”. These specifications are always arrived at through continual trial and error, testing and refinement. In supply chain, its impossible to source products, evaluate potential suppliers, or manage inventories or demands, without specifications. It is those specifications which will measure what will be acceptable, and what will not. For this reason, sourcing is often executed after much or all the BOM has been established. However, this is far too late and ensures delays, and risks failure in the development process. Instead, supply chain must work hand-in-hand with engineering through the design process, considering possible sources, and manufacturers in concert with the engineering effort. Supply chain also needs to engage possible suppliers for advice (particularly for any item made to specification – but not exclusively since “off the shelf” products must also be fully specified and understood) to understand manufacturing limitations and opportunities for efficiency. All of this must be gathered and relayed back to engineering as meaningful data, and engineering can then reciprocate with design iterations that are viable from a supply chain point of view. The importance of revision control Of course, as the design is evolving a tremendous amount of time and effort will be lost if there is no mechanism in place to track the evolution as well as documenting every change and the specific reasons for the change. For engineering, this is the process where all the learning and intelligence (IP) around the product is developed and retained. So it is also true with supply chain, as supplier and component strategies depend on understanding the intimate details (and challenges) of every specific part. Supply chain is sometimes affected by revisions, and other times is the cause of revisions (supply problems OR possibilities of better items/technologies become available) but a complete knowledge of the evolution is required to strategize and optimize the supply chain as well as manage day-to-day operations once in production. Shared ownership is no ownership While the BOM is the connective tissue between engineering and supply chain, responsibility for the BOM, its revisions and specifications lie squarely with engineering. Why? Because the BOM is the stated design intent of all components relative to the end product (or in other words, relative to the system they must work together in). Design intent cannot be shared jointly by supply chain and engineering, nor should it ever be. Likewise, responsibility for supplier relationships, strategies and sourcing methods lie squarely with supply chain and cannot be shared with engineering. These are, in effect the “design intent” elements of the supply chain system and production execution that must produce those specifications dictated by engineering. While both design intent and supply/execution strategy inform and influence each other, anything less than a clear delineation of ownership will make everything run amuck in short order. When creating a supply chain from scratch, the finished BOM is only a snapshot in time. The knowledge generation, supply strategies, and overall viability of the supply chain is made or broken by the journey to the BOM, not the BOM itself. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 5 - Supplier Management Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch: Part 3 – The Planning Hierarchy: unlocking the path forward7/27/2021

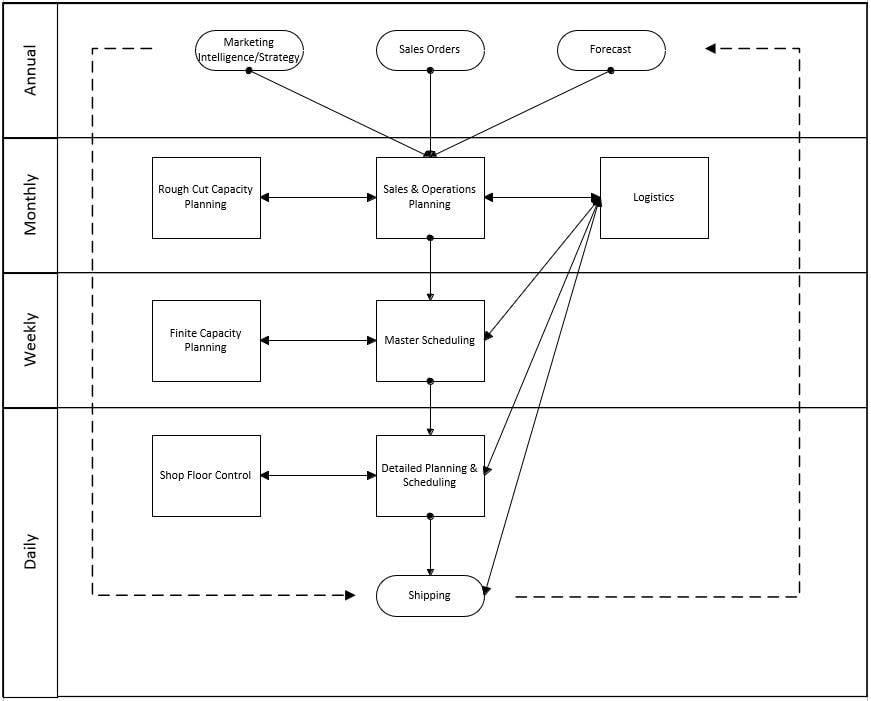

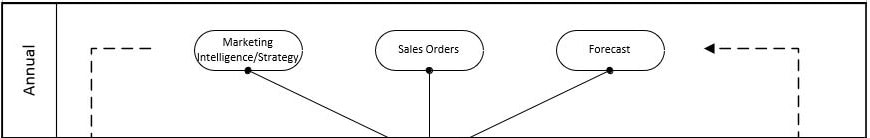

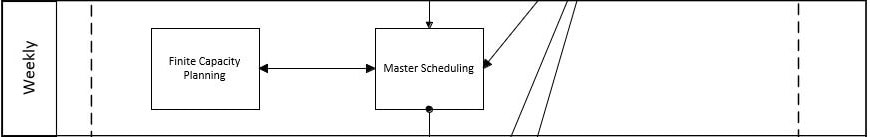

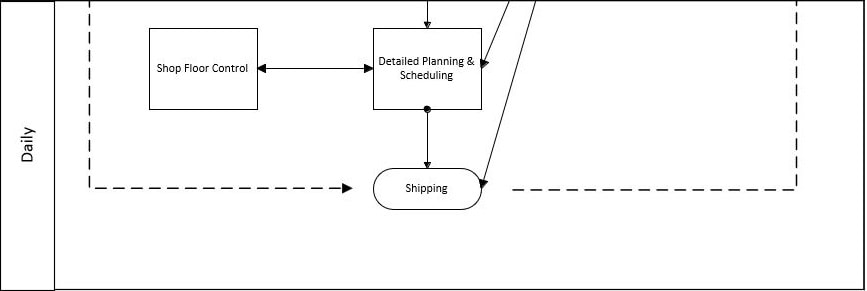

In part 2 of this series, I talked about the chaos of the very early stages of any company, or product and how to approach that chaos as both infinite complexity but also infinite opportunity. Since its neither practical nor productive to try to create a product or supply chain system that is all things, to all customers, all at once, we’ve got to apply some boundaries to the complexity and opportunity. We need to focus – on the data, activities and risk/reward opportunities that will best bring us toward our goals. Preferably with the least amount of time, effort, and cost wasted as possible. The planning hierarchy is the structure and the lens through which to achieve this. And, as a structure it allows you to apply a System Thinking approach to planning your product and your supply chain. The structure is applicable to any company that produces a physical product, regardless of if they are a start-up, or a well established multi-national giant. The key however, is in how to apply it. To understand that you have to have a relentless focus on your customer, and your business case to provide value to that customer as well as to the business (if the business cannot generate value, it won’t be a business for very long!) The hierarchy is the roadmap, how you decide to get there will determine your operations strategy and the overall success, profitability, and sustainability of your company. The further we go down the planning hierarchy, the more detailed and short term our decisions (and repercussions) become. But each level needs to be aligned to supporting the business case above all else. A typical planning hierarchy (applicable to any manufacturing company) appears as follows: Applying this framework to a start-up In a start-up (as with any company) things need to be considered from two views simultaneously from day one: how will decisions impact the project/company today, and how decisions impact the project/company tomorrow and beyond. Building a brand-new supply chain from scratch is no different, since project or business decisions made today can have implications and costs that the company will have to bear for weeks, months or possibly for the entire product life-cycle including cost, risk, effort to produce, and agility to react quickly to changing market conditions. For start-ups it can be difficult, if not impossible, to know all that you need to know for success. This is the complexity or chaos I’ve mentioned previously. In order to overcome this, most start-ups will forgo any consideration of supply chain and focus on marketing and product engineering while leaving supply chain to a later date when there aren’t so many variables. In most cases, these firms will invest time and money into developing a product, only to have to do much or all of it a second time to produce a product that can actually be viable for manufacturing and supply chain, that will actually generate a profit, and will deliver measurable value to the customer. This time lag can be deadly to early-stage companies, who will either run out of funding or simply be beaten to market by a better organized competitor. Instead, I argue that the planning hierarchy can be adopted to meet and overcome these complexities during development, not after. And the process will result in a purpose-designed supply chain that develops concurrently with the product. Let’s walk though some ways to apply this. Business Level Considerations (Annual Outlook/Consideration) At the top of the planning hierarchy, your supply chain must consider the business case. The business case is the anchor. If this isn’t solid, anything tied to it will be no better. At the top of the planning hierarchy are the long-term and broad concerns to be responded to. Long term considerations:

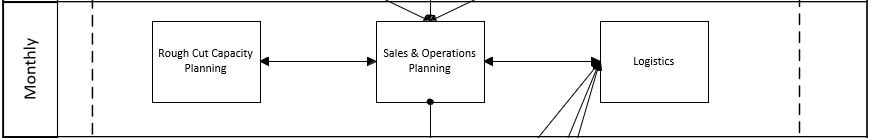

While nobody can expect to understand these elements fully (especially sales forecasts) for a new product or for an early-stage firm, it’s worth mentioning that they need to be understood as well as they can be and be constantly challenged when new information is available. The business case grows and matures in this way, and the complexity of the supporting planning hierarchy will grow and mature accordingly to support it. In the planning hierarchy, these are usually annual considerations since to change direction in any of these elements requires a major reworking of all supporting systems. It is also important to note that this is why supporting systems should be no more complex then necessary, for maximum agility in times of crisis. Operations Considerations (Shorter term, typically monthly) Once the business case is identified, vetted and validated, product development can begin in earnest. There may already be some napkin sketches or even conceptual models, but now all that must be tempered with the requirements of the business case. The development will look up to the business case and also any available feedback from potential customers or markets as a guide. Operational considerations:

Inputs and outputs here can, and will, change more frequently than the business case, especially in product development because new information is learned as the development cycle progresses. In a production environment, this is a monthly exercise. But in a start-up, it should be considered at any decision affecting the product development and design. A criticism I have often heard is “why spend that time for things that are only conceptual, isn’t that waste?” The answer is a firm no. All of this work, if documented, becomes your supply chain knowledge base specific to your product and it will inform both your design and your supply chain strategies as you go. It will orient your products and your operations towards viability at first, and competitive advantage over the long haul by steering you clear of pitfalls and avoidable challenges. Detailed Production Considerations (Weekly) In production, this level of detail is a weekly review cycle, but in a start-up, it becomes something completely different. Start-ups that are just developing their products aren’t engaged in capacity planning or master scheduling of production. Instead, consideration needs to be given to how, at a detailed level, your product will be produced based on the development done to date. Detailed production considerations:

Figuring these out post-development is far too late, and will force a re-do of much (or all) of the development cycle to re-align with the realities of supply and resources, before any real production can happen. The opportunity here for a start-up, is to really research what resources are available and weigh cost against value. This is where you can build your database of who is out there, and what they can offer and share that with the development team. Its also a good opportunity to build relationships and vet ideas with potential manufacturing or supply partners who are subject matter experts. This is where the heart of your new supply chain – data guided by knowledge, will start to grow. Daily Execution Considerations At the bottom of the hierarchy is all the detailed day-to-day considerations of producing your product. In production, this would include daily activities around the shop floor – scheduling machines and people, daily material consumption and replenishment, as well as shipping and receiving (both your finished goods to customers, but also incoming supply of materials) to name just a few things. Ultimately, the details at this level will determine your profit margin, your quality, and your ability to satisfy the customer. In many ways the work done at higher levels will frame how effective work at this level can be. For a start-up, this can be applied as additional detail to the elements already described when considering specific aspects of the design and how it will be produced in scale. Considerations for daily operations:

Bringing it All Together This is just the beginning. There is more that can be done to apply this hierarchy to a start-up, in order to streamline development and build a viable supply chain concurrently. Much more in fact than I can touch on in a short blog. But hopefully this illustrates how this framework can serve to cut through complexity and unlimited variability inherent in start-ups with a repeatable, scalable supply chain structure that can grow with the firm and guide the product development towards successful execution, by designing and developing with the end in mind the whole time. The effectiveness of the end result be governed by your supply chain, for better or worse. They key to remember is that it is never too early to start this process. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 - The Bill of Materials - The Journey is At Least As Important as the Destination Part 5 - Supplier Management In part 1 of this series I discussed some fundamental ideas and approaches required to start from scratch and build a supply chain system. If you take those to heart, you will find that you are immediately confronted with incredible, unlimited complexity and variability around what to do next. I call this chaos, that which is unknown, impossible to know, and virtually impossible to plan for. In an early-stage company, or at the earliest stages of any product development, chaos is all that exists. Chaos can present itself to organizations as:

We are told that we need to plan, set rules, buy technology, and invest capital with the promise that we will eliminate chaos. But how do you eliminate that which is unknown and impossible to know? Embrace the chaos We are taught to view chaos as a bad thing. I argue that creativity in its purist form is chaos, and no innovation or leap of progress can be made without it. A music composer takes infinite complexity, the unlimited chaos of sounds, colours, and emotions and blends them into a masterpiece. Successful businesses don’t spend much time trying to avoid chaos, instead they manage those things that are within their control and build processes that can respond ever quicker to changing complexities and those things they can’t control. Life is chaos, to attempt to live life chaos free is futile. If you are at an early-stage and building a supply chain from scratch, then you owe your very existence to chaos. Your new firm or product idea was born because existing companies or products failed to respond to some changing need, some complexity, some type of chaos. It is up to us to embrace and harness the power of chaos. A balance between order and chaos In part 1, I mentioned that you need to focus on those things which you can control. Those controls are required to ensure that your firm operates consistently, predictably, with known costs, benefits, and measurable progress for any given activity. In supply chain, this means that there is a hierarchy or universal organization of elements which must exist (and must exist as an interactive system) before any of those elements can function well. Back in the day, we referred to it as “the planning hierarchy”. My former professor and mentor, the late Lloyd M. Clive (co-author of the seminal book “Introduction to Materials Management”) used to tell me “tattoo that hierarchy onto your brain, and you will be able to navigate any conceivable supply chain challenge". After 20 years of testing that assertion, I can confirm that he was exactly right. However, and this is critical, this structured approach should not be applied to prevent chaos. Instead, consider that it is required to bring your focus where it needs to be to consistently and predictably manage what is known while also harnessing chaos by providing a system flexible enough to learn and adapt on a dime. Processes for process’s sake – an unmeasurable waste I have seen countless firms build process upon process, implement technology upon technology, in order to “improve performance” without consideration of the overall business case, or without a system thinking approach. This approach is flawed. The inevitable outcome is a strict, inflexible set of policies and processes which do the opposite of perform, they absorb capital and time (an unrenewable resource) and most often end up existing for the sake of existence. We’ve all just witnessed a great example in real life with young start-ups pivoting to fill PPE needs faster than the well-established firms could react, and go on to prevail in delivering value to their customers. Start-ups are full of chaos (unlimited complexity), while mature firms are full of order (constraints applied to reduce complexity). But its chaos that demands order to constantly evolve. The planning hierarchy need not be complicated, in fact its better if it's not. It should be continuously measured and reviewed against the business case, to ensure that it is controlling that which can be controlled, predictably and reliably. And the business case should be continually measured against performance to the customer needs. Anything beyond that is waste. Early-stage firms will require only basic elements in their planning hierarchy, and if any of them become more effort to manage than the benefit they provide, you have to consider that it may be going too far. Consider Continuous improvement, a well-known (and important) part of effectively managing process. But if there is a shift in the business case, or processes are no longer supporting the business case (ex. dominant focus on local-level performance metrics instead of system-level) firms are at risk of creating more waste in continuous improvement instead of improving performance. Dr Russel L. Ackoff, a pioneer in System Thinking once said “Continuous improvement isn’t nearly as important as discontinuous improvement.” And indeed, he was right. Discontinuous improvement is chaos. It is step-function change, as opposed to gradual ongoing improvement. It’s also the ability to pivot and adapt quickly when conditions or requirements change unpredictably, or when the customer demands it. For early-stage companies, the adoption of process controls and best practices is not nearly as important as adaptation of principles to the specific situation of the firm or the product. Putting it together I usually tell those who are building a supply chain from scratch, to embrace the chaos but keep that seatbelt on. Process and a hierarchy are required to reduce the chaos to manageable terms, but the key is to adapt these to the firm's needs, not to adapt the firm to the process needs. If viewed with a system thinking mindset, the task of balancing chaos with order will be dictated by how well the firm understands and delivers to its customer. Chaos allows the firm to be creative, and well-developed order allows the firm to quickly adapt to changing conditions with greater speed, ease, and repeatability However, it’s critical to remember that the customer is the most important part and process must never consume more than the value it delivers. In my next post, I’ll explore the planning hierarchy in detail and how it becomes the foundation for any firm’s supply chain (and operations), and how it can be adapted to early-stage firms. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 - The Bill of Materials - The Journey is At Least As Important as the Destination Part 5 - Supplier Management  As applied to organizational improvement, system thinking is grounded in the following fundamental principles:

System thinking takes a birds-eye view of how the firm is employing the resources it has invested in in delivering value to its customers. System thinking posits that a firm’s resources do not operate independently, but work together in an interconnected and interdependent fashion, not unlike the musicians in a world class symphony. System thinking focuses on aligning and synchronizing the flow of activities among and between each resource as they collaboratively work together to create and deliver ever-increasing customer value. When should we use a system thinking approach? Any organization interested in improving its operational and financial performance should employ system thinking. System thinking is a different way of viewing and thinking about how your organization creates value for the customers that buy your products and/or services. In a business environment, system thinking focuses on delighting the customer by significantly improving flow in the value creation stream in your firm. The focus on customer value creation distinguishes system thinking from conventional cost-driven management approach. Simply stated, cost-driven management breaks down the organization into its individual resources, products and services, then focuses on driving down or optimizing the cost of each resource in isolation. Unfortunately, this approach not only results in sub-optimal system performance but also ignores the only part of the system which generates cash inflows and future growth, the customer. System thinking as a best practice focuses on aligning and synchronizing the activities of all resources in a system. In the process, waste is eliminated, lead times are shortened, labour is freed up, capacity is released, costs are reduced, operational and financial performance is improved, and the firm becomes increasingly competitive. This approach will also effectively reduce a firm’s carbon footprint by reducing the production of greenhouse gases through the elimination of wasteful non-value adding practices. Organizations are constantly facing new challenges, and the future is unknowable. The current pandemic adds additional layers of complexity and volatility into an already challenging hypercompetitive marketplace. As a manager or business owner it can be overwhelmingly difficult to determine what the next step should be for your business in this increasingly complex environment. System thinking helps clarify and simplify the way forward. If your organization is struggling with any of the following issues, system thinking can help.

BKW’s Business Alignment Program BKW can help you resolve the challenges you are facing, and help you insulate your firm from the myriad of complex challenges you are faced with every day. Our Business Alignment Program based in system thinking is a proven approach. It will help you to identify hidden opportunities, release untapped capacity, and improve your business’ resiliency. If you are a small to medium sized manufacturing firm and anything you’ve read above resonates with you, we can help and would like to hear from you. Please click the link below to provide us with some preliminary information and BKW team member will contact you to discuss how we can help. Click here to contact the BKW team. “How do I establish a supply chain? What are the most important elements of a supply chain for a start-up or early stage company? How can I build supply partners when I don’t have any volume yet?” These are the most common questions that I hear from start-ups and early stage companies, and they are excellent questions! How do you create a supply chain when you have very few people, minimal resources, low volume, and next to no budget? In Canada more than 90% of our manufacturing firms are Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), and that number is growing rapidly. Unfortunately, most supply chain discussions and methodology are focused on improving already existing operations for larger firms, often with more capital and higher volumes of production than the majority of SMEs. As an entrepreneur, this is incredibly frustrating. From a supply chain perspective, a business that bases its revenue on producing tens and hundreds of something can be harder to manage than continuously improving an established supply chain that has scaled to mass-production due to the extreme variables in cost, time, customer and supplier terms, etc. Although, with the onset of COVID-19, even the well-established methods being put to the test. Shifting consumer values and economic conditions are changing the way companies produce - high-volume, low mix/value production is giving way to low volume high mix/customization/value products and services. Here in Canada, we are well positioned to be global masters of low volume, high value products. Products in this category include items such as mission critical medical devices, scientific equipment, and consumer goods designed for a market where longevity, quality, and sustainability are prioritized over cheap and disposable products. However, this model is infinitely more complex with far more variability than traditional high-volume manufacturing. Building a supply chain from nothing is an entirely different science than anything that applies to the mass-manufacturing world. Today I’ll give you my 4 best tips for establishing your supply chain. 1) Focus on What You Can Control If you find yourself in a company that’s establishing a supply chain for the first time, then odds are that you have some sort of business education or career experience. You may have formal supply chain training, as I do. If that experience has been focused on well-established supply chains, you may find starting from zero to be an overwhelming proposition. Worse, if you are rigid in “how it should be done”, you may find that it’s almost easier to forget what you know than to try to determine how to apply it to completely different circumstances. Traditional standards and best practices from large or well-established firms and/or mass manufacturers are often just not practical for early stage or low volume/high value producers. Today with COVID-19, business conditions can change hourly (forget daily) and that level of variability can’t be met with incomparable past experience. So, the first step is to shift to a mindset that doesn’t try to control variables that we can’t (with incomparable experience) and instead focus only on that which we can control. We do this through system thinking and evidence-based decision making. 2) Understand that Supply Chain is not a thing or a standard, it’s a result that is dynamic and constantly changing. Supply Chain is a result, not an independent function or activity. It is the result of several cross-functional business processes and how well (or not) they work together. You can’t build or refine a supply chain as an individual entity; you must build better business processes and integrate them with a system view (focused on the business case and delivering customer value - or not producing anything customers aren't willing to pay for) which will result in better supply chain performance including resilience and agility. That’s not to say that supply chain will “build itself”, but rather what you do build as supply chain can only be as good as the business processes to which its connected, and all of it only as good as the whole-system view and value chain. This is why Supply Chain is a strategic function, despite common ideas that it’s a transactional or administrative function. Supply Chain is the ultimate measure of your overall business system in real time, and your focus on delivering value to your customer. 3) Supply chain begins long before you have a physical product. I’ve often seen firms get a working prototype and announce that they are now ready to consider supply chain and manufacturing, only to find out that much of the work they have done must be undone and redone (at the expense of time and cost) because what they developed is not manufacturable or able to be supported with supply in the volumes, costs or quality required. The resulting delay to market or unplanned capital requirements can be deadly. In reality, your supply chain considerations begin sometime after someone has a product idea but before its first iteration is scribbled on a napkin. You need to have input from professionals within the various disciplines that are collectively called “supply chain”. As a new product idea iterates from vision, to napkin, to proof of concepts to pre-production prototypes, the supply chain iterates also and in parallel. To me, it can’t be anything other than a fully integrated development cycle. While the product designers, engineers, product managers, marketers and sales team are working to create a product that a customer is willing to pay for, supply chain folks (sourcing, purchasing, logistics, materials/inventory/production management) as well as potential suppliers (for individual products, or contract manufacturers) must weigh-in to advise what is possible to produce within the constraints of cost, materials availability (short and long term) lead time, as well as international trade concerns, shipping regulations, quality standards, etc. The supply chain begins as an evolution of an idea, grown by the acquisition and validation of information and resources that are ultimately tuned to the business case and customer demands. It identifies areas of risk, and often facilitates negotiation and trade-offs between different areas/interests in a firm to arrive at the best and most viable outcome from an execution point of view. If all the functions involved have done their due diligence along the way and validated customer needs against identified constraints of delivering those needs, the end result will a manufacturable product that provides value the customer is willing to pay for. It is important to note that there are two customers to consider - the external customer who buys, and the internal customer who depends on information. Access to these professional skill sets can be tricky for early firms, in many cases it can be far more economical to hire professionals on an as-needed basis so long as you understand how to properly integrate those resources within a system thinking framework that supports your business case. 4) Remember Everything You’ve Learned but Keep an Open Mind While in step 1 above it may have felt like it would be better to forget everything you know, in this step you may realize that you have the opportunity to apply portions of your past experience that (with testing, modification, or improvement) may be adaptable to this new product or business case. And other portions may be completely inappropriate to the specific business case and should be left behind. But until you are ready and willing to throw it all out in favour of a wide-open mind, then you are subject to the same old enemies of progress: “I’ve always done it this way”, and you cannot see the opportunities that lie hidden in the knowledge gaps that everyone has, which are uncovered through collaboration. This shift in mindset is the single biggest factor that will make or break a young company or product, because it limits one’s ability to adapt old knowledge with the present conditions, and create new knowledge and experience that is highly relevant to the firm right now and down the road. While it sounds trivial, its actually harder than one may think. In a future blog, I’ll discuss the most important functional elements required to establish a supply chain system from scratch, in any firm. Want to read more in the Creating a Supply Chain from Scratch Series? Click the links below:

Part 1 - Understanding What a Supply Chain is and When to Start Establishing Your Product's Supply Chain Part 2 - Understanding Chaos and How to Work With It Part 3 - The Planning Hierarchy: Unlocking the Path Forward Part 4 - The Bill of Materials - The Journey is At Least As Important as the Destination Part 5 - Supplier Management Knowledge Transformation and Digitalization of Supply Chains More and more these days we’re seeing a call for digitalization and AI adoption in supply chains. COVID-19 revealed the weaknesses inherent in global supply chains, and the call has gotten louder. With that, the onslaught of folks pushing their wares has begun…everything from small apps to large enterprise level solutions promising to revolutionize your business and make your supply chain “resilient” or “risk proof”. It all sounds alluring, and awesome. I can’t think of anyone who wouldn’t want to take advantage of anything that will help get their operations back up and running. But as we get caught up in the excitement, we may not spend the time to properly consider options, and consequences. When the excitement wears off, the realities may seem far less appealing over the long term. Why – is it a mistake to look to technological solutions? Did our selected provider lie? Are many of these solutions just gimmicks? The answer is a firm “No” to all these questions. Caveat Emptor Caveat Emptor is the most ancient supply chain principle. It’s Latin for “Let the buyer beware”. It means that ultimately, responsibility rests on the purchaser to check something out thoroughly, perform diligence and investigate all data before acting on a purchase, and if any of this is omitted, then the buyer will likely end up unhappy with the results. Perhaps this concept has become more relevant than ever. At a macro level, our supply chains didn’t fail the COVID-19 stress test because of any lack of digitalization or AI. They failed because of a lack of sufficient knowledge to build strategic and resilient supply chains in the first place. Moving from a macro to a micro level, this translates into operational problems at firms: costs that are hard to manage, expedites and late shipments, shortages in supplies and materials, lowest unit-cost decisions, inability to determine total costs including process costs, and many more. The lack of knowledge, not a lack of technology, places supply chains in a purely reactive state (always too late) instead of it being a strategic asset (always ahead of the challenges). And this is what needs to change before firms will get ahead of the curve - regardless of technology. The good news is that it can change, with leaders emerging everywhere to help guide the knowledge transformation. These are my four steps for firms that are considering digitalization: 1) Get your house in order first Well-built technology tools are absolutely accelerators. However, it’s up to firms to make sure their operations and supply chains are up to the task BEFORE implementation. This is not a new concept. ERP, which has been around for decades, typically requires anywhere from 9 months to a year of whole-company organization before it ever goes live for this very reason. And every failed ERP implementation I’ve ever seen or been asked to correct, has been a direct result of firms short-cutting or skipping this portion entirely. It’s far more economical to get your firm in order first and not expect digitalization to do it for you, that’s not its function. Reputable providers of digital and AI solutions geared for supply chains actually don’t want you to buy their products until you’ve sorted out what you supply chain needs to look like thoroughly and accurately, according to your specific business requirements. Why? As one of them explained to me, “Our solution is a Ferrari. It will accelerate what the user applies it to exponentially. If the user applies knowledge and experience it will do incredible things. If it’s applied to a bad set-up it will become exponentially bad, exponentially quickly, and with a lot of cost. If we sell a Ferrari to someone who doesn’t know how to drive…it will look great and maybe even go really fast for a short while, but it will end up in disaster and our customer will blame the software. We’d rather see the customer be successful and our tools be a part of that success.” 2) Use external parties to give you an unbiased view If you’ve read this so far and said “we’re in great shape, we don’t need to sort anything”, then it’s time to get another firm to do a detailed analysis of your firm to validate what’s real and what’s perceived. Preferably, not the same firm that you will buy your digitalization solutions from to avoid product bias. All firms have built-in internal bias due to departmental metrics, goals, and targets which often may support the individual departments (and even contradict other departments) instead of the business as a whole. The only way to overcome this is to use an external party not bound by any of those metrics (or compensated on meeting those metrics) who can apply an integrated system thinking approach to the business and guide re-alignments where needed without any internal bias. 3) Allow only validated data to guide the technology solution selection If you’ve done 1 and 2 above you’re now in a position to take the validated data and really understand what the core needs of the business are, without distraction of “symptoms” and “fires”. You can now look at solutions that will, when applied appropriately to your specific business needs, reduce or eliminate your pain points and allow you to increase your capacity or bandwidth (depending on the nature of the technology tool in question). Technology cannot ever be a replacement for knowledge in any business. It can however be an accelerator, freeing up resources to allow redeployment of those resources on higher-value functions to support the business case. Expecting technology to help manage your business is a great approach. Expecting it to do it for you leads to trouble. 4) Be mindful of your technology landscape and develop a strategy I once knew of a firm that had 17 different software solutions for different aspects of their business. It was a nightmare. The firm began to hire folks to keep up with the double and triple data entry these separate tools required, and it snowballed from what started as a way to minimize costs, to something that increased their costs 10-fold and nearly eliminated their capacity to actually deliver to their customers. All the while, there was no consistency or accuracy in the data provided by these separate tools. Though this sounds extreme, it can happen more easily than you think, especially among separate departments. The best practice is to develop a technology strategy from the outset. Your technology strategy should work to centralize your data and make sure all areas of the organization are getting the same numbers. Well-tuned enterprise systems are good for this, and they are accepting more “plug-ins” that allow you to add functionality from different providers without decentralizing your data (or access to it). We are truly beginning to see an integrated, system thinking approach where technology solutions are concerned. But we humans still need to do the hard work of selection, implementation, evaluation, management, and adaptation of technology wisely, as we still possess the most advanced technology in the known universe - that which lies between our ears. Technology is neither good nor evil, it is only what we make of it. If we have a bad experience with an implementation or a specific piece of software, we really need to take an unbiased look at the underlying business conditions before we blame the tool. Caveat Emptor. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed